Art (Click images below to enlarge)

Artist Statement

Ground Truth: Monitoring and Measuring the Social Geography of Global Climate Change

Video from the Ground Truth installation is available at www.andreapolli.com.

What impact has the ubiquity of computerized devices had on public understanding of the environment in light of the climate crisis? How has the public participated in the process of weather and climate data collection and modeling? Are new structures for public participation developing? Can artworks contribute to a change in these cultural practices? Can artworks function as a driver or catalyst for social change?

With these questions in mind, last year I had the opportunity to go to Antarctica for two months, on a National Science Foundation-sponsored artist’s residency where I worked alongside scientists studying the global implications of Antarctic weather and climate change. The Antarctic is unlike any other place on earth: geographically, politically, and culturally. Larger than the U.S., it is a frontier where borders and nationalities take a back seat to scientific collaboration and cooperation, a place where the compass becomes meaningless yet navigation is a matter of life and death. It is an extreme environment that holds some of the most unique species, but it is also an ecosystem undergoing rapid change. 2007/2008 marks the fourth International Polar Year (IPY), the largest and most ambitious international effort to investigate the impact of the poles on the global environment.

Prior to my trip, I had spent several years working in collaboration with atmospheric scientists to develop systems for understanding storm and climate information through sound (a process called sonification). I created a spatialized sonification of highly detailed models of storms that devastated the New York area; a series of sonifications of actual and projected climate in Central Park, the heart of New York City and one of the world’s first locations for climate monitoring; and a real-time multichannel sonification and visualization of weather in the Arctic.

I wanted to go to Antarctica to find a way to more closely engage with the issue of global climate change. I had been using data from remote weather stations in my projects, though I had never actually visited them. While in Antarctica, I spent most of my time in two places: The Dry Valleys (77°30’S 163°00’E) on the shore of McMurdo Sound, 3500 km due south of New Zealand, the driest and largest relatively ice-free area on the continent, completely devoid of terrestrial vegetation. It is a terrain of frozen lakes, glaciers and mountain rocks that many scientists believe may be similar to the terrain of Mars in the past. I also spent time at the geographic South Pole (90°00’S), the center of a featureless flat white expanse, on top of ice nearly nine miles thick.

In researching how I might approach a project in this unusual setting, I looked for inspiration from history. I made a connection to the writings of the early-20th-century explorer Admiral Richard Byrd. In the diaries of his solo winter-over at a remote Antarctic camp, he writes of being alone and slowly poisoned by a faulty heating system yet unable to live without this warmth. The weather instruments he monitored were the only things that provided him with solace:

“I was not long in discovering one thing: that, if anything was eventually to regularize the rhythm by which I should live at Advance Base, it would not be the weather so much as the weather instruments.”

Unlike Byrd, my focus in Antarctica quickly shifted from the instruments to the people. I learned that many more people are stationed in Antarctica to observe and record weather and climate than are machines, and that the scientists call this process of observation ‘ground truthing.’

Why, with sophisticated instrumentation and remote sensing, do we depend upon humans on the ground to look up at clouds? What is it that the machines are missing and what is the human role in understanding what is unfolding? What is the meaning of ground truth and can it inform and enhance our relationship with the environment? These are the questions I am exploring in my current series of works called Ground Truth. Ground Truth presents interpretations of data, interviews, and documentation of weather observers and scientists as they discuss, maintain, and gather data from remote sites.

In interviews with scientists about this subject, I was struck by how many spoke about the importance of non-quantitative knowledge. I thought that only numbers would matter to the scientists, but this was not the visceral experience of a site, but I was surprised to find this was not the case at all. For example, Dr. Andrew Fountain, the head of the Dry Valleys Long Term Ecological Research Group, said:

“Just because you have the data doesn’t mean you understand the system. It’s important to come down and view the landscape and in our case view the glaciers, and see how the glaciers are reacting to these changing environments. And that feeds into our understanding and our non-quantitative knowledge.”

This interview, as well as audio and video interviews with nearly 20 other science researchers, along with a preview of a short video documentary, raw sound recordings, images, video clips, and project updates are accessible to the public on my website www.90degreessouth.org.

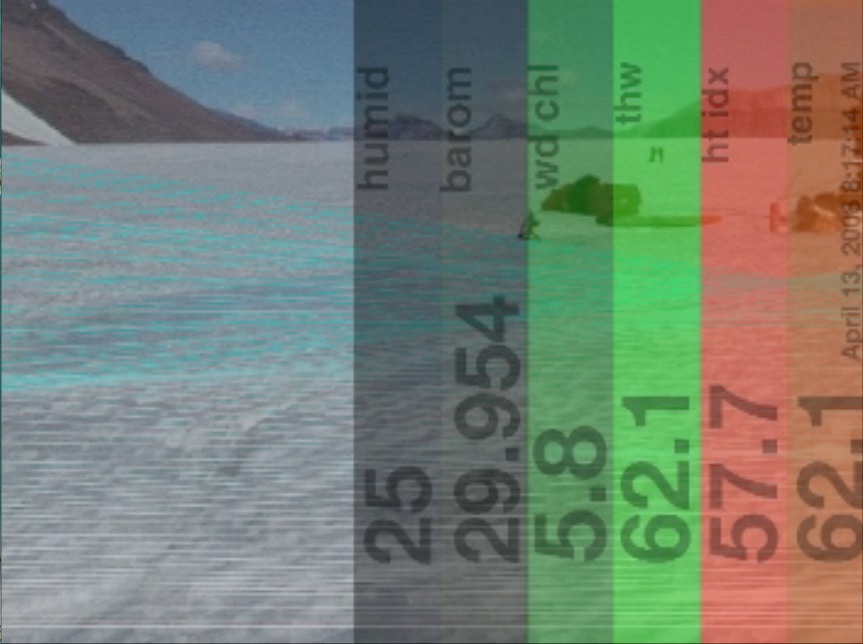

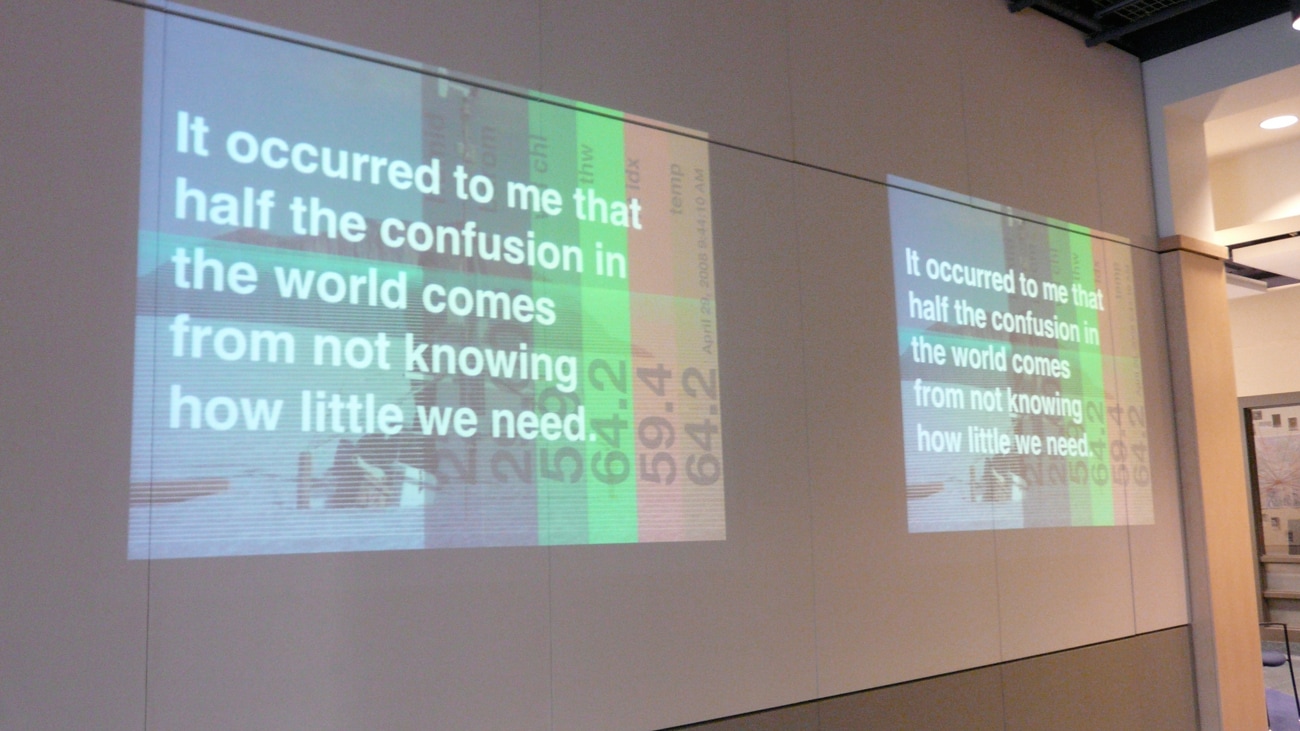

In addition to the video documentary, part of the Ground Truth project is a temporary public art installation consisting of a modified weather station interpreting data in real time. Audiences experience the instrumentation used by scientists and learn about the data being collected through visualizations and sonifications. The station has been installed at the Atlas Center for Art and Technology in Boulder, Colorado and will soon be installed at Eyebeam in New York City.

Despite the developed world’s climate-controlled interiors and easy access to all kinds of fresh produce at any time of year, our lives are still dependent upon the weather and climate. With global warming, our dependence is becoming even more apparent. In part, the purpose of giving the public access to climate and weather information and instrumentation helps people understand our connection to the atmosphere and promotes greater harmony with these natural forces.

Writing nearly 100 years ago of the harsh Antarctic environment, Richard Byrd realized that living simply, in touch with the earth’s natural rhythms, is not only possible, but actually beneficial:

“It occurred to me then that half the confusion in the world comes from not knowing how little we need.”