Daughter’s Wisdom

In 2021, when my oldest daughter was four and a half, I was toweling her off after a bath when she thoughtfully remarked, “My heart is a girl. Is she four and a half, too?” I replied, “Your heart is four and a half. But it started beating when you were still inside my body, before we started counting your age.” Our conversation reminded me of how gender, age, and what constitutes life are interwoven social constructs, and ones that are contested with serious consequences. My interaction with my daughter illuminates how centering the physical body can prompt us to think differently about issues like aging, diverging from the dualistic Eurocentric thinking that imagines aging as a linear rise and fall of mind and body. 1

Introduction

Scholarly and mainstream discourses often overlook ageism compared to other axes of oppression even though it produces detrimental consequences that require attention. 2 This article engages aging at the intersections of race, class, gender, dis/ability, and movement, using critical dance studies and critical yoga studies to analyze how three aging women of color leverage their yoga, dance, and other movement practices toward what Sonya Renee Taylor terms “radical self-love.” 3

Although the three women focus on their yoga practices over other movements, this essay engages dance studies approaches to offer a critical intervention to discourses on aging by analyzing how bodies and their movements create and express knowledge and interact with social structures. Most disciplinary fields, even critical yoga studies, omit the insights that can be gleaned from body postures, movements, and sequencing. But bodies and their arrangements can offer complex, varied, and generative meanings. 4 Because movement forms are fluid and experienced subjectively, they can be imbued with a variety of different and even contradictory meanings, demonstrating the plethora of politics and possibilities that bodies can contain and convey. 5 A dance studies analysis, which considers the power and meanings of bodies and their movements, offers a way into challenging mainstream assumptions about aging.

The stakes of combating stigmas about people’s bodies are high. Social constructions have material effects on bodies and their mobilities. This is evident in the overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous people and people of color in prisons and detention centers, which limits their movements, and in the architecture and infrastructure that prevents or inhibits disabled people from accessing public and private spaces. 6 Because dominant social structures can operate to extinguish marginalized people, the act of survival, which necessarily entails aging, is radical. As Taylor writes, “Radical self-love is a world free from the systems of oppression that make it difficult and sometimes deadly to be in our bodies.” 7

To examine how ageism manifests in movement practices and how dance studies offers a different lens, I conducted three interviews with women of color yoga practitioners and teachers. These interviews illuminate how movement modes, yoga in particular, can be leveraged to reinforce and/or subvert dominant social structures, including ageism, racism, classism, sexism, and ableism. Based on close readings of these interviews, I offer the concept of “radical movements” to think about physical movement as political movement. Movement modes like yoga and dance can challenge discrimination against non-dominant people and communities and present alternative paradigms for facilitating individual and collective healing and wellbeing, including mass social movements. 8 My use of the term “radical movements” draws on and extends scholarship in Native and Black studies, specifically Native scholars Cutcha Risling Baldy and Melanie Yazzie’s thinking on “radical relationally,” by focusing on bodily movements as conveyers of knowledge and change connected to political activism and organizing. 9

Using a dance studies lens allows me to emphasize how movement itself can be radical and disruptive to the status quo. I draw on the work of dance and performance studies scholars Michelle LaVigne and Megan V. Nicely, extending their work on radical bodies, movements, and gender to also examine age. 10 If, as Taylor writes, “a radical self-love is a world that works for every body,” how do movement modes, and yoga in particular, nurture or interfere with such “radical self-love,” particularly for the aging woman of color’s body? How can one theorize the movements of the aging body as, to borrow again from Taylor, “a pathway towards personal and collective transformation?” 11

In this article, through close readings of interviews, I first articulate how mainstream perceptions of age in the US are embedded in movement practices and interwoven with other dominant structures. I explore how the interviewees have leveraged embodied practices to create alternative paradigms for aging, or what I call radical movements. To counter the pervasiveness of Eurocentric binaries and reveal the knowledge inherent in movement, I conclude by asking whether thinking of the slower movements of the aging body as normative, as perfect, as ideal, may provide possibilities for radical “mass movements that are necessary for staging a serious counterhegemonic challenge to the status quo of death that currently structures our existence,” in particular, US capitalism. 12 Drawing on dance studies, how might celebrating, rather than stigmatizing, the slowness of the aging human body challenge mainstream common sense about aging, including capitalist logics, which prioritize speed alongside efficiency and productivity?

Methodology

One of the challenges in writing this article was the potential to offend people by interviewing them about aging. I had initially intended to reach out to a broader group of women who are Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) with whom I had previously collaborated, but when I went to write the email requesting their involvement, I decided against it. Although everyone ages if they are lucky, I understood that some people just do not want to talk about themselves or their work through this lens. I decided to create a call for participation from aging BIPOC women practitioners of yoga so that people could self-select. In May 2021, I advertised on Race and Yoga journal’s Facebook and Instagram pages. Race and Yoga is the first peer-reviewed journal in the emerging field of critical yoga studies. I co-founded it in 2011 and now serve as its Editor-in Chief. It emerged from the Race and Yoga Working Group at UC Berkeley, which I founded in 2011 as a doctoral student working amidst a dearth of scholarly and mainstream discourse on yoga from an intersectional approach. 13 In total, three BIPOC women replied to the call.

Jocyl Sacramento was a friend and colleague with whom I attended graduate school at UC Berkeley. Misia Denea and I had met briefly at the 2016 Race and Yoga Conference. Saku and I had never met in person or virtually. 14 All of the women were based in California. Two resided in the San Francisco Bay Area and the third lived in Los Angeles. As might be expected of people connected to Race and Yoga, all the women expressed a critical understanding of intersectionality. They are all women of color who individually identify as of African descent, Filipina, or Sri Lankan. One of the women identified as queer. The other two discussed heterosexual relationships. Their ages ranged from thirty-nine to forty-four. One of the women declined to give her exact age, but referred to herself as an “aging millennial,” meaning she was born between 1981 and 1996. 15 Two of the women discussed their desire to have a child in the future. According to contemporary medical discourses, their pregnancies would be considered “geriatric.” 16 The relatively close and relatively young age range of the three women I interviewed may reflect who is active on Race and Yoga social media sites and who considers themselves aging. It may also highlight how aging is both a social and biological construct: Who acknowledges they are growing older, and who wants to talk about it?

I interviewed each of the women for approximately one hour via phone or Zoom, depending on their preference and, drawing on the scholarly practices of ethnic, gender, and dance studies, examined their lived experiences in relation to my own. 17 I am of Filipina, European, and Native ancestries, and I also identify as a woman of color. I recently turned forty, and I am a yoga practitioner and teacher. Although I was working with a small sample of participants, my hope is that our collective insights about movement practices and how they can both reify and thwart dominant ideas about aging will help expand scholarship at this juncture. 18

Movement Practices for Radical Self-Love

1. Limitations

Each of my interviewees discussed how their lived experiences with yoga and other movement practices, including dance and cycling, had the potential to be healing even as they were entangled with dominant structures. Misia Denea has been a dancer since the age of five. Today she is a body positive yoga instructor and the founder and owner of Hatha Holistic Integrative Wellness. She identifies as an aging millennial of African descent. In regard to the dominant expectations she has encountered in dance, Denea said:

If you’re going to be a choreographer, you have more shelf life. As someone who’s viewed as having a female body, your shelf life as a dancer, in ballet, it’s over in your early twenties. But if you do modern dance or hip hop or ethnic dancing like West African or Afro Latin or Afro-Caribbean dance, it might be a little bit longer. But you’re still at the end of your prime basically by your mid to late-twenties. And you’re an old dancer by the time you’re in your thirties. 19

Denea’s use of the term “shelf life” is instructive. The word is defined as “the length of time for which an object remains usable, fit for consumption, or saleable.” 20 This again underscores how not conforming to dominant structures can produce detrimental economic consequences. When I asked Denea why she thought the shelf life was longer for dance practitioners of African forms, she said, “It’s just the European aesthetic. Youth is super prioritized. Having a youthful look about you is just super prioritized for ballet dancers. I’m kind of glad I didn’t do anything that was super competitive because a lot of those people also have eating disorders.” 21 The enduring European aesthetic tends to portray the colonizers’ beauty ideals, such as light features and slender figures, as superior and antithetical to those of the colonized. As Denea notes, some dance forms like ballet have historically cultivated and perpetuated a white European ideal, including long limbs, certain kinds of flexibility, seemingly curve-less bodies, and youth. 22 For dancers, the tight association between youth, thinness, color, and ability can create deadly consequences when depriving, altering, and starving a body can seem like the only path to remaining employable.

Ballet is not alone in reproducing these norms. Yoga spaces can also prioritize dominant Eurocentric aesthetics in ways that can be dangerous and alienating. Vinyasa offers one useful example. Quite popular in the contemporary US context, Vinyasa is a style of yoga characterized by a sequence of yoga postures and seamless transitions. The practitioner, guided by their breath, moves or “flows” from one posture to the next. In her interview, Denea stated:

I don’t practice Vinyasa anymore. When I did, I noticed many of the most popular teachers were thin, conventionally attractive. What I mean is the European standard: white women or women who have white features. Maybe they were good yoga teachers, maybe they weren’t. What I mean by good or bad is, were they knowledgeable of the history of yoga, and anatomy, and yoga philosophy? I think a lot of the most popular teachers were sexy, conventionally attractive. They wore shorts or midriffs to class. I think these classes were well attended because you were going to have fun and get a workout. Maybe there’d be some yoga in there. But I feel like in the Vinyasa world, what I was finding were these Barbie-doll-looking white women on the covers of, like, Yoga Journal or whatever other popular magazines. I think the landscape is changing because there are definitely people, activists and organizers, in the yoga world trying to shake that up. But I remember going to Vinyasa classes, and they would be like, if you go into Ukatasana, it’d be like, ‘Oh, this is a great way for you to tighten your butt.’ That’s not why I was going to yoga. 23

As Denea indicates, dominant social norms can infiltrate yoga spaces as well as yoga practices, including the patriarchal and economic pressure to wear revealing clothes to sell an experience and the promise of an idealized body. Many people understand yoga as a holistic practice and even a pathway to enlightenment, 24 which is certainly not exclusive from joy, but what Denea points out about participants’ goals “to have fun and get a workout” suggests a detachment from the original purpose of yoga practice. 25

Jocyl Sacramento is a thirty-nine-year-old Filipina who works as an assistant professor in Asian American and Ethnic Studies and lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. In her interview, she was explicit about the link between movement practices and patriarchy. “I grew up with two brothers and my older brother often told me I couldn’t do things because I was a girl. I was determined to prove him wrong all the time. I tried to show him that I could do things. And sometimes I could be better than him. And so, it’s definitely patriarchy that has informed my introduction to embodied practices.” 26

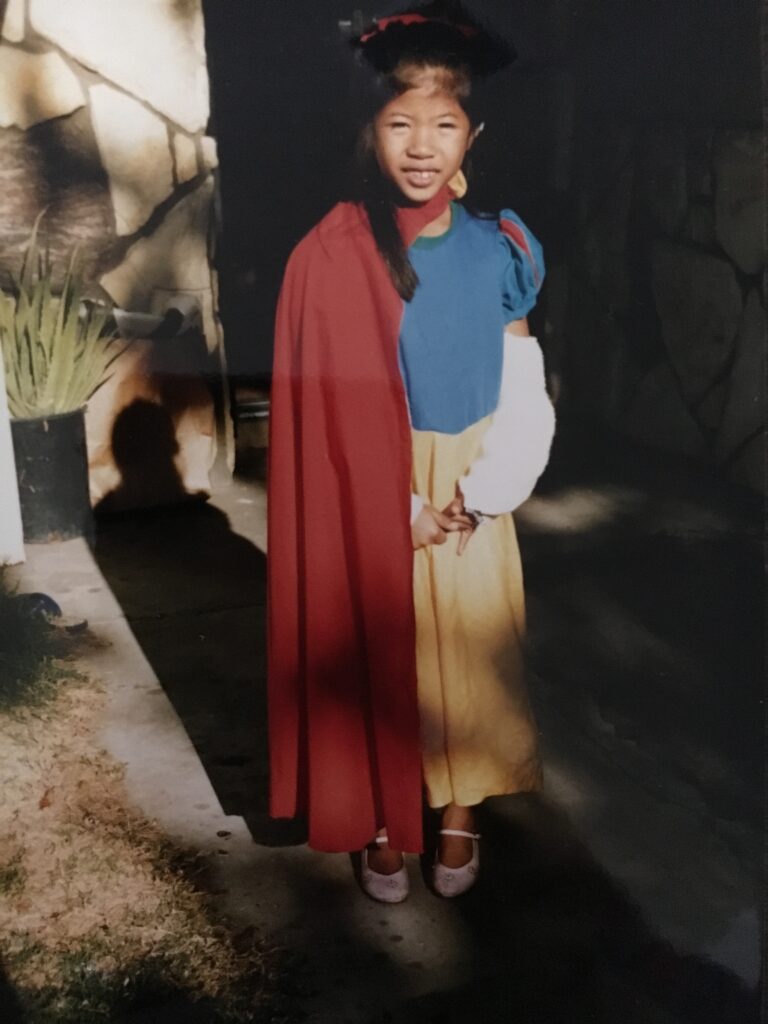

For Sacramento patriarchy was simultaneously an axis of oppression and a source of motivation. Although she felt the pull of competition, she also noted that it can be intrinsic to patriarchal thinking and our fear of aging, pointing out how young women are often pitted against older women, with fairy tales like Snow White emblazoning these ideas in our collective unconscious as common sense. She also pointed out that this competition between young and old, beauty and ugliness, serves capitalism by feeding the anxieties that drive people to purchase things like anti-aging creams. Of course, the term “anti-aging” is a misnomer. The only thing these creams can do is conceal or soften certain physical changes that come with age, like wrinkles, inconsistent skin tone, greying of the hair, and other similar changes. 27 Although most people know that these products do not prevent aging, there have nevertheless been class action lawsuits filed accusing companies of deceptive advertising, which goes to show how powerful is the drive to remain young. 28

Saku is a forty-four-year-old Sri Lankan yoga teacher, performer of Bharata Natyam, and a musician. In our conversation, she focused on anti-aging stigmas that detrimentally impact women. I asked her what she thought about women not sharing their age, to which she said,

For our generation and above, aging is like [laughs] the worst thing that can happen to a woman. Aging is, you know, Oh, you’ll get old and your husband’s gonna leave. You have to stay looking young to keep a guy interested in you or you’re not going to be able to get a man. There’s a whole lot of get a man, keep a man vibes we were brainwashed with, I believe. So the older ones especially, I think they don’t want to share their age because they want to look young or feel young or have people have the impression that they’re young forever. [Laughs] I think this is changing with the younger ones, but I think with my generation and up, it’s like, Oh, don’t tell anyone your age. You know. People won’t want to be with you if they find out how old you are. Or they might, I don't know, they might think you’re old. Like being old is a curse or something. 29

Similar to Sacramento, Saku focused on the effects of a male-dominant society that socializes people to view aging negatively, especially women. Saku referred to this as “patriarchal brainwashing.” 30 I include Saku’s laughter in this excerpt because it highlights the absurdity of the stigmas surrounding aging. In describing her experience, Saku linked women’s concerns about aging to marriage and to economics. She had been in what she called an “unsatisfactory” romantic relationship, but her family pressured her to get married because the man had monetary wealth. 31

My family wanted me to be with that guy because he was well-to-do, but my happiness didn’t matter. My age, the age was a big deal too. Like, Oh, she needs to get married quick. Then it was like, Well, if you leave him, how are we going to find somebody to marry you? And it’s like, Oh, because you’re getting old, nobody’s going to want you when you’re old. There was a lot of that. A lot of that. And then on top of that, I have dark skin. So that makes me even more undesirable in my culture. 32

Saku’s final note about colorism offers an important reminder of how dominant norms can be internalized and perpetuated by non-dominant people and communities. 33

Like Denea and Sacramento, Saku also discussed the infusion of yoga practices, particularly those often offered in gym and studio settings, with workout mentalities. 34 However, all three women also discussed their holistic practice of yoga and other movement forms, which went beyond the physical. This, I argue, is one way to counter dominant stigmas surrounding aging.

2. Possibilities

Although everyone spoke about the ways that dominant structures have shaped their lived experiences and relationships with movement modes, they also highlighted their own and others’ agency to choose their physical practices, how they engage with them, and how they think about them. These radical movements offer alternative paradigms for people and communities’ healing and wellbeing. Counter to the normative obsession with physical appearance, the women engaged in movement practices for holistic purposes. 35 They frequented spaces with people of color instructors, including those that catered to the experiences of women, trans people, and people who are nonbinary. In contrast to viewing aging as strictly a downhill and individual process, the interviewees described aging as joyful and connected to positive relationships and responsibilities. 36 However, even when movement modes present possibilities for creating alternative paradigms for aging and radical self-love, there are still limitations and contradictions.

Each of the women emphasized the holistic benefits of yoga to nurture their wellbeing and sustain the work that they were doing. Although such holistic benefits can indeed uphold the capitalist system by enhancing workers’ endurance and productivity, they may also serve as a source of healing and survival for nonnormative people and groups, including women of color. Denea said, “You can certainly get fit with yoga. I’m not saying that you can’t. But that was never for me as a survivor of PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Yoga was helping me on so many levels that it didn’t really matter whether I was going to lose weight or look like a track star.” 37

Similarly, Saku discussed practicing yoga at times twice a day, before and after work, to relieve stress. This was when she was teaching music at a public high school in South Central Los Angeles where the teacher turnover rate was approximately one every two months. 38 She said, “I wanted to do it every day just to feel good. I wanted to do it in the morning before I went to work to be a school teacher, especially those days when I was teaching in a really high stress kind of environment. Yoga before work was very, very helpful for me. Sometimes I would come home and put in a VHS tape and do yoga after work.” 39 Saku remained at the school for ten years. She left in 2009 after being laid off “like many arts teachers all around the country,” she said. 40 Although yoga helped Saku, claiming that yoga operates exclusively as a counterhegemonic practice oversimplifies things because it also sustained Saku as a worker within the capitalist system.

Sacramento described having suffered from anxiety and depression and likewise appreciating the holistic value of yoga. Her relationship with various movement modes has shifted as she has aged. It is, she says, “less about the physical and more about the spiritual and holistic impact that these practices have on me.” 41 Such an approach to movement modes also points to how aging may be understood beyond its impacts on one’s physical appearance, and instead as a “spiritual and holistic” process and practice. Sacramento said:

Now that I’m older I value everything that these practices bring to me, instead of just the physical aspect. When I was younger, I was really concerned with my body and what my body looked like. Now that I’m older, I’m more concerned not only with what my body can do, but also how I feel, and how the practices I’m engaging inform how I see my worth. Yoga has definitely informed how I see myself and my mental wellness and my emotional wellness. Just the meditative piece of it has brought more calm to my life now that I’m older and juggling so many things in life. The practice has helped me stay grounded as an aging person with more responsibilities. 42

Along with emphasizing how aging has shifted her engagement with movement modes, from a focus on the physical benefits to an appreciation of their holistic value, Sacramento highlighted that these practices have shifted her sense of self-worth. 43

Like Sacramento, Saku spoke about how her relationship with yoga has changed as she has aged. Her practice and pedagogy have expanded to incorporate political frameworks into her practice, what she calls decolonizing yoga. 44

I appreciate yoga more with my age, the different aspects of it. I think when people are younger, or just new to yoga in general, they just like the asanas [poses]. They don’t like all the other aspects of yoga. They’re not interested or they don’t have time for it or whatever. In America, the focus is on asanas. Everything else about yoga is boring or too Indian or whatever they want to call it. But now, I feel with the age, I appreciate it. And then there is also the decolonize movement, which made me think, Okay, well, if I’m going to decolonize my classes, I’m going to bring it back to how it’s supposed to be, or in that direction. 45

As Saku has aged, she has developed more patience, which has made certain aspects of yoga, beyond the asanas, more appealing. She is particularly moved by Trāṭaka, a meditative practice in which a person stares at a particular point. 46

All those eye exercises and looking at a candle. I’m in my forties. My eyes are not the same as they were in my twenties and I’m starting to feel it a little bit. Now all of a sudden Trāṭaka makes a lot of sense when ten years ago it might’ve been boring. I don’t want to say it was boring. I liked it personally, but I never imagined I would teach Trāṭaka one day. I didn’t think anyone in America would ever want to learn Trāṭaka. I thought it would be too boring for people. But because I’m interested in decolonizing yoga, let’s get that Sixth Limb of yoga in there, focusing on meditation. And that is good for aging eyes, and people looking at screens, and everybody is doing that now.” 47

In addition to moving toward decolonized practice, another way to facilitate radical movements and radical self-love is to cater to nonnormative bodies and conceive of people beyond the female-male binary. 48 Denea shared how this manifests in her practice of Iyengar yoga, a form founded and developed by B.K.S. Iyengar, which emphasizes bodily alignment and precision in the poses, incorporating blocks, blankets, and straps to be used as props. This attention to proper alignment and precision benefits all bodies and, perhaps in particular, aging bodies, which often require additional care to prevent injury. Although some people misperceive props as solely a tool for beginning practitioners, Iyengar yoga uses these aids to provide benefits to all. In addition to the practice’s unique use of supports, practitioners hold poses for a longer duration and with more instruction from their teachers than typically occurs in Vinyasa yoga classes. Denea described yoga teacher trainings in the Iyengar lineage to support practitioners dealing with menstruation or menopause, dealing with stiff legs or hot flashes, or, as she said, “whatever else comes along.”

Every person experiences menopause differently. I know how to give them alternative yoga poses. You’re not going to get that in Vinyasa class. It’ll be like, Go into Child’s Pose until you’re ready to join us or something. In the Iyengar community, they’re trying to do away with calling these classes ‘women’s health’ and calling them instead ‘womb health’ or ‘wellness,’ which I totally support because you don’t have to be a woman. It’s beyond gender, you know, who has a womb and who doesn’t. 49

The Iyengar classes that Denea discusses are forms of radical movement because they attend to bodies in various conditions and strive to be inclusive beyond the male-female binary.

For Denea and Sacramento, their yoga practices have positively influenced how they feel about aging, countering what they previously associated with a downhill process. 50 Denea stated:

I love yoga because I know what it’s like to accommodate my body and other people’s bodies and people who have different experiences. I took a workshop right before the [COVID-19] pandemic with somebody who knows how to make adjustments and yoga sequences for people who have MS or neurological issues. People have issues like that with their nervous system as they get older. As far as my yoga education goes, I’m prepared to get older and to help other people feel comfortable getting older. 51

Sacramento shared how centering people’s wellness and humanity in learning spaces, including schools, is often overlooked. In her view, attending to these issue can help shift the dominant discourse surrounding aging. She said:

What kind of relationship do you want to have with your mind? What kind of relationship do you want to have with your spirit? What are the practices that we can use to maintain our wellness? Traditionally, wellness has not informed how we teach and this is not a value within schooling practices. So how can you bring that? How can you bring wellness into the mix? How can we bring wellness to the conversation on what knowledge we value? I think it comes back to what is informing our knowledge about aging and our bodies, and then, how do we shift that to be more humanizing to ourselves and to one another. 52

Both Denea and Sacramento underscored the potential for people to shift their understandings of aging to a positive process and for this view to ripple outward in pedagogical settings, creating positive change for the individual and collective.

3. Classrooms and Teaching Spaces

One of the key points that emerged in my conversations with all three of the women was the personal and political importance of instructors of color and affordable classes. When Sacramento was in the doctoral program at UC Berkeley, she had a whole spreadsheet detailing where to find instructors of color, their classes, and new student specials that made the classes affordable. 53 Speaking from her perspective as a scholar of race and pedagogy, she said:

It’s important to see someone who looks like me teach the class because I’m very cognizant of the practices and how colonialism and imperialism have informed how they have made their way to me and to the United States. It’s important for me to see someone who looks like me because I know that we have a shared experience, whether through family or cultural values. But it’s also about representation. The experience [of taking a class from an instructor of color] was completely different because they brought in issues like oppression and injustice. So it felt like, when they were teaching me or guiding me, they knew the different struggles that I went through, which is something I haven’t experienced with white yoga instructors. Being able to incorporate that into the actual pedagogy that they have in the class is so important. I also research race and pedagogy, and I know how important having people of color teachers are to student success. The research says that when students see someone who looks like them in the classroom who also has a critical perspective, it actually improves their success in that particular class. I mean, it’s definitely about having someone who looks like them, but it’s also about having that critical perspective attached to being a person of color, or Black, Indigenous, or a woman of color that changes the way in which the pedagogy is impacting students. 54

Reflecting on her SoulCycle gym class, Sacramento describes her own experience having an instructor of color.

I go to a Filipino instructor. That’s really important for me to see someone who looks like my brother. When I go to his class, the way he talks about building power is very motivating for me. It’s not about where I’m going to go on this bike that takes me nowhere but about the resistance. When I’m thinking about the resistance, that can mean so many different things to me as a scholar of Ethnic Studies. When the instructor talks about it, he tells us to add more resistance, and I’m like, Oh, hell yeah. I’m going to add more resistance [laughs]. Resistance has been defined in so many different ways but when I add resistance in my last class, I think about Black, Indigenous, and people of color resistance movements. I also think, This is going to make me stronger. 55

Certain words or instructions, which may be commonplace, when spoken by an instructor of color, gain higher meaning because they are translated through the shared experience and critical perspective brought by racial oppression. For Sacramento, conceptualizing physical resistance as counterhegemonic motivates her to push harder in class.

Like Sacramento, Saku connects her yoga practice with political work in other contexts, and makes this explicit in her teaching. She works with the organization Food Not Bombs, particularly active during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-2021, making and delivering over 100 free vegan meals per week to people who were unhoused and living on Los Angeles’s Skid Row. 56 Throughout the lockdown, she raised money through donation-based yoga classes that she taught on Zoom and donated the proceeds to Food Not Bombs. 57 One of her customs is to encourage her students to think about how they can extend their yoga practices beyond the mat, which seemed to differ, in her experience, from many white yoga instructors. 58

I asked Saku how she navigates what she believes is important and what her students want, anticipating that there may be a conflict. She said:

You know what, I did lose some people, and that’s cool. Like they want a gym class. There’s plenty of other white yoga teachers. You can go to a Vinyasa class. But if you want a South Asian experience with a South Asian teacher, here I am. And I’m still giving a workout and a stretch like these white folks do. You know, you’re getting [the workout and stretch] along with, Oh, by the way, how are you getting your karma yoga in? Or how are you practicing restraint or how are you working on your self-study? You know, I’m bringing up the other parts of yoga. I’m starting to talk about it while they’re in a pose. Stuff like that. But I’m still making them work. It’s still an awesomeness class. It’s a journey for me too. I’m starting to be more like, Oh, you’re going to do it my way. I’m not going to worry about like, Oh, white people, they won’t like it, they’re going to think I’m too Indian. I mean, that’s already been an issue. Since I was a little kid. I don’t want to be too Indian or too Sri Lankan, too brown, too, too, too. Like that whole assimilation game. 59

Instructors of color, subjected to stereotypes based on their race, bear additional burdens, which can increase when their pedagogies do not conform to Eurocentric norms and desires. But with that burden, as Saku reflects, comes opportunity for transformation.

While it is vital for this work to be done by people of color, Denea pointed out that white instructors seem to be grappling with how they can contribute to change too. In an industry that has been appropriated and dominated by white instructors and practitioners, there is plenty of work to do to make space for people of color in all roles, to make classes financially accessible, and to engage ethically and critically with the practices. Denea said:

Most of [the Iyengar yoga teachers in the Bay Area] are white. Only one of my senior teachers who I’ve been practicing with for several years now is a Black woman. I think that’s changing in the Iyengar community. And I think what is clear is that COVID was the main pandemic people were focused on, but there were multiple pandemics that were exposed during 2020 [such as racial violence]. And I think as a result of the George Floyd uprising people everywhere had to reflect and have a moment of awareness around how they’re addressing race and racial tensions in their respective industries. It looks like the Iyengar community, at least in the United States, is trying to have a reckoning with making their landscape more diverse. It’s mostly well-educated, affluent, white people and East Asian folks [as both teachers and practitioners]. Less often you’ll see Black or Indigenous people in class or as teachers, but they’re there. It looks like those in leadership are making an effort to change the landscape as a result of the multiple pandemics. 60

Some of the ways that studios are making this change include sliding scale fees and free classes, scholarships, and classes specifically for people of color. During the pandemic, Denea was in a class with a Korean American instructor. It was an intermediate class for Black and brown practitioners. “I really enjoyed that. It was really nice. Most of the time in Iyengar, and like I said, I’ve been practicing Iyengar for six, seven years now, I’m the only person of color in class. The only queer person in class. The only person in my tax bracket.” 61 Although there remains work to be done to address accessibility and racism in the yoga world, these concrete steps do make a difference for practitioners and teachers alike.

The digital realm and social media in particular operate as another kind of classroom. These have proven to be spaces of possibility for counterhegemonic work in yoga and beyond. Saku described how teaching yoga on Zoom freed her from the financial cost and time commitment of traveling to teach her classes, and this has given her more freedom to teach what she feels is important. 62 She also described how social media has been critical to the shifts in thinking about who is a yoga teacher and practitioner because, as one space more democratic than others, it allows users with non-dominant perspectives to circulate ideas and insights often excluded from mainstream media. 63 It is on social media where people find critiques of white yoga teachers, their practice and overrepresentation, and find alternative perspectives and representations, those of Indigenous people, people of color, and people whose bodies are marked outside the norm.

On Aging

Saku, Denea, and Sacramento all viewed growing older as joyful and fabulous. Rather than looking at movement as an exclusionary barrier to older bodies, they saw the potential for yoga and other modes to alleviate some of the physical challenges that come with aging. When I asked Saku what she wanted people to know about aging, she said,

That aging [can] be a fun journey. That there is wisdom that comes. I would not trade my gray hairs for the misery of my twenties. My life is so much better now than back then. I was trying to make my family happy [staying in that relationship], not having self-esteem because, Oh, I’m dark, and I’m whatever, you know, just trying not to be difficult, because they always call me difficult. A woman’s quality of life matters. And you know, across the board, women or trans or the oppressed people, people want to keep us down. But the quality of our life matters, you know? We’re allowed to have a happy life, too. Everybody deserves happiness and basic decency and respect at the minimum. And that includes with age, too. And it’s possible to get older and have fun. It doesn’t mean your body is falling apart and getting miserable. I mean, yeah, your body is falling apart, but yoga can help. 64

Denea also spoke to the health benefits of yoga for aging bodies, and she strives to view aging as joyful and filled with exciting possibilities.

I was watching an interview with an Italian Iyengar teacher who is seventy, and she’s like, Oh my God, look at all these books I have to read about yoga and yoga philosophy. She’s like, I hope I don’t run out of time. She has an excitement about learning about anatomy, learning about yoga philosophy. And she’s just worried about running out of time. She’s not worried about, you know, dying tomorrow. One of her students is ninety years old and is still doing Sirsasana [Headstand]. They’re not slowing down. I want my life to be like that as I age. 65

Staying active and physical can help people feel like aging does not mean slowing down or losing out on life. I wonder, however, whether embracing slowness might offer one way to counter capitalism and experience aging as ideal. I discuss this further in the conclusion, offering a possibility for slowing down while remaining active.

Aging can be understood as an individual process, but, because we are social beings, aging also inevitably affects relationships with others, intimately and on a generational scale. Saku talked about how her perspective on her actions changed as she got older. She now saw herself as someone whose actions could have an influence on younger generations, particularly her nieces. About leaving an unhappy relationship despite family pressure and the anxiety of being unpartnered while aging, she said, “I’m showing the youngsters that they don’t have to keep doing this. They can do it a different way. I’m trying to make it look fun and fabulous.” 66 Sacramento felt similarly. She and her partner recognize that they are role models for their son. “When my partner became a father, he was really concerned about how our son saw him in terms of what he did in his life. He wanted our son to know that he took care of his body. Now he’s like hella working out and doing intermittent fasting. The idea that we are models for the generations has informed our relationships to our bodies.” 67

Sacramento also powerfully described how aging can lead to more responsibilities and a “shift in care.” 68

My siblings and I are all adults now. This term “adulting” has come up in our conversations. You know, having to pay a mortgage and having to pay bills has definitely changed the way that we feel about ourselves. And maybe that’s also tied to responsibility. Our aging is informed by how many things we’re responsible for. And my brother and I are now parents. We’re raising children. There was definitely a shift in care. When we were younger, the elders cared for us. I was raised by my grandparents. Both my parents worked. And then when my grandmother was older and she was no longer able to care for herself, it was really about us taking care of her. It’s a conversation, who’s caring for who. 69

As one person grows older, their relationships to others change, and for a time, people take on caring responsibilities, whether for children, parents, grandparents, blood or chosen kin, until it is their turn. It is a radical way to think about aging: that this process can bring the individual closer to community and strengthen relationships. Additionally, the communal gathering that takes place in yoga and other movement practices and the imperative to move together provide a powerful metaphor for human co-existence.70 Even as humans practice alone, they move collectively. This could be extended to say that even as people age alone, they age collectively. This offers a helpful counterpoint to the mainstream approach to aging in which older people are deemed useless or undesirable and removed from the public eye, more with each year that goes by, in material and immaterial ways, placed in assisted living facilities or subject to social neglect. Saku, Sacramento, and Denea’s reflections offer departures from the dominant conceptions of aging, pointing us toward a model of aging as ideal.

Conclusion: Aging as Ideal

Mainstream society is obsessed with youth and physical appearance. 71 Although children’s insights are often devalued, adults also have a limited shelf life, to borrow from Denea, that cuts off somewhere around thirty-five or forty. 72 The experience of growing older in this society is also inextricably connected to the experience of ableism, racism, colorism, sizeism, classism, sexism, and cisgender privilege. This is all to say, even though humans all do it, aging is set up as a failure. But it doesn’t have to be. This article offers the concept of radical movements to challenge these life-limiting ideas and the structures they create, which discriminate against elders and all who are outside normativity with real life-and-death consequences. As an alternative paradigm for aging, the concept of radical movements emerges from the experiences of women of color, particularly from their yoga practices. This alternative model understands aging to be a lifelong, holistic process and celebrates growing older. It recognizes and values the contributions of all while centering those who are marginalized. It also views aging in connection to relationships and responsibilities, including caring for others. However, along with all of this potential, radical movements can also be assimilated into mainstream and counter-radical projects. This is evidenced, for example, when corporations offer free yoga to their employees, providing health benefits that sustain workers in the unhealthy conditions of a capitalist economy. 73

As people age, they do become slower. In a capitalist society that values speed and efficiency, slowness carries negative associations. From the outset, yoga offers an intervention with its primary aim to slow down the body and the breath. Drawing on dance studies methodologies, perhaps we may think of the aging body as becoming closer to the yogic ideal, and a site of radical and counterhegemonic possibility. Aging does not necessarily mean the absence of movement or movement ability. Furthermore, even if one loses mobility and appears not to move, there remains much movement essential to life, however invisible, in every body. An alternative paradigm for growing older honors the slower, aging body as a state of aspiration, and recognizes the aging body in connection with other bodies, structures, and possibilities for radical personal and collective transformation. 74

WORKS CITED

Blu Wakpa, Tria. “Decolonizing Yoga? And (Un)Settling Social Justice.” Race and Yoga 3, no. 1 (2018): i–xix.

———. “Hozho Yoga: Indigenous Movements Illuminating Human and More-than-Human Interconnections.” In Practicing Yoga as Resistance: Voices of Color in Search of Freedom, edited by Cara Hagen, 133–55. London: Routledge, 2021.

———. “Meditation.” Photograph courtesy of Tria Blu Wakpa.

———. “Settler Colonial Choreography and the Divided Body: Performing Masculinities Through the Switch Dance at a Native American Prison Powwow.” Lecture, University of Michigan Center for World Performance Studies, February 19, 2020.

———. “Sky Reaching Pose.” Photograph courtesy of Tria Blu Wakpa.

Calasanti, Toni M., and Kathleen F. Slevin. Age Matters: Re-Aligning Feminist Thinking. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Carruthers, Charlene A. Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements. Boston: Beacon Press, 2018.

Case, Anne, and Angus Deaton. Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021.

Cave, Bryan. “Beware of Making Unsubstantiated Anti-Aging Claims.” Lexology, April 7, 2017. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=735f63cf-3d00-45d7-8777-bc0c8616c04d.

Chatterjea, Ananya. Butting Out: Reading Resistive Choreographies Through Works by Jawole Willa Jo Zollar and Chandralekha. Middleton: Wesleyan University Press, 2004.

DeFrantz, Thomas, and Anita Gonzalez, eds. Black Performance Theory. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014.

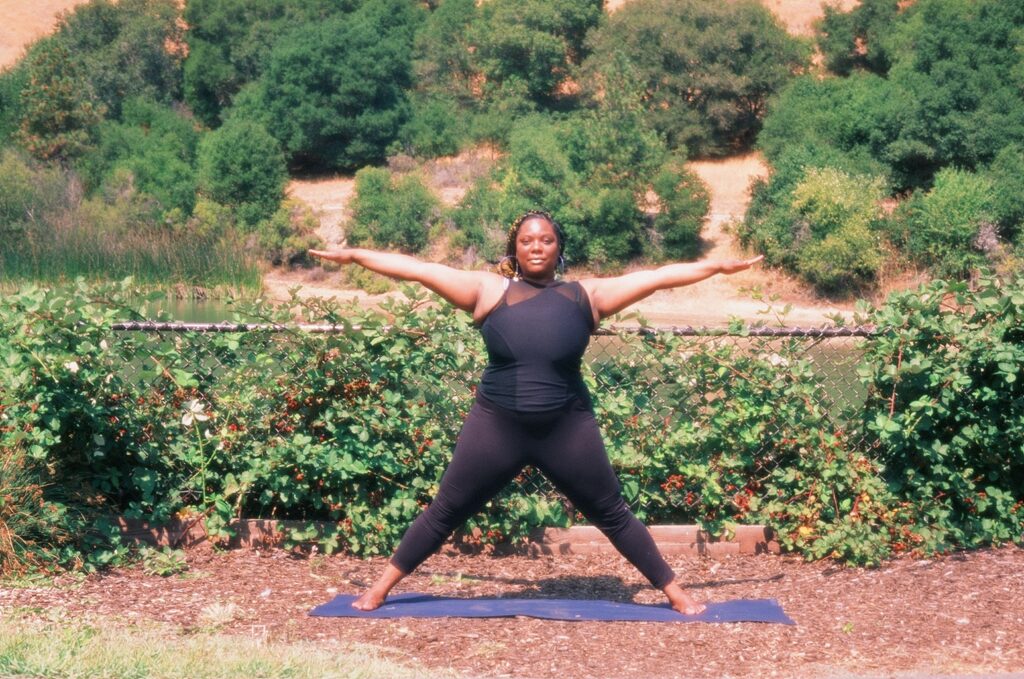

Denea, Misia. “Goddess Pose.” Photograph courtesy of Misia Denea.

Dimock, Michael. “Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins.” Pew Research Center, January 17, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/.

Food Not Bombs. “Food Not Bombs: Our Story.” Accessed June 28, 2021. http://foodnotbombs.net/new_site/story.php.

Goeman, Mishauna R. “(Re)Mapping Indigenous Presence on the Land in Native Women’s Literature.” American Quarterly 60, no. 2 (2008): 295–302.

Kelley, Robin D.G. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Boston: Beacon Press, 2002.

Lahey, Joanna. “Age Discrimination in the Workplace Starts as Early as 35.” PBS News Hour, January 15, 2016, sec. Economy. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/age-discrimination-in-the-workplace-starts-as-early-as-35.

LaVigne, Michelle, and Megan V. Nicely. “Curating Dialogue: The Bridge Project’s Radical Movements.” TDR: The Drama Review 62, no. 4 (2018): 143–53.

Mason, Andrew. “What’s Wrong with Everyday Lookism?” Politics, Philosophy & Economics 1, no. 21 (2021): 1–21.

McNeill, William H. Keeping Together in Time: Dance and Drill in Human History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Nakajima, Nanako, and Gabriele Brandstetter, eds. The Aging Body in Dance: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Native Lives Matter. Lakota People’s Law Project, 2015. https://s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/romeroac-stage/uploads/Native-Lives-Matter-PDF.pdf.

Neumark-Sztainer, Dianne, Allison W. Watts, and Sarah Rydell. “Yoga and Body Image: How Do Young Adults Practicing Yoga Describe Its Impact on Their Body Image?” Body Image 27 (December 2018): 156–68.

Novak, Alison C., and Nandini Deshpande. “Effects of Aging on Whole Body and Segmental Control Whole Obstacle Crossing under Impaired Sensory Conditions.” Human Movement Science 35 (June 2014): 121–30.

Roberts, Rosemarie A. “Radical Movements: Katherine Dunham and Ronald K. Brown Teaching toward Critical Consciousness.” Dissertation, City University of New York, 2005. https://www.proquest.com/docview/305004779?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14512.

Sacramento, Jocyl. “Snow White.” Photograph courtesy of Jocyl Sacramentol

Saku. “Garland Pose.” Photograph courtesy of Saku.

Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Singleton, Mark. Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Sood, Sheena. “Towards a Critical Embodiment of Decolonizing Yoga.” Race and Yoga 5, no. 1 (2020): 1–12.

Strauss, Elissa. “From ‘geriatric Pregnancy’ to ‘35+ Pregnancy’: There’s a Better Way to Talk about Pregnant People.” CNN Health, June 9, 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/06/08/health/pregnant-less-offensive-language-wellness/index.html.

Strings, Sabrina, and Tria Blu Wakpa. “Rethinking Yoga: Meditations on the Work We Do.” Race and Yoga 1, no. 1 (2016): i–iii.

Taylor, Sonya Renee. The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love. 2nd ed. Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2021.

Tin, Sim Sai, and Viroj Wiwanitkit. “Trāṭaka and Cognitive Function.” International Journal of Yoga 8, no. 1 (2015).

Wendell, Susan. “The Social Construction of Disability.” In The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability, 35–56. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Wong, Yutian. Choreographing Asian America. Middleton: Wesleyan University Press, 2010.

Yazzie, Melanie, and Cutcha Risling Baldy. “Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and the Politics of Water.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, and Society 7, no. 1 (2018): 1–18.

- Mishauna R. Goeman, “(Re)Mapping Indigenous Presence on the Land in Native Women’s Literature,” American Quarterly 60, no. 2 (2008): 295–302; Tria Blu Wakpa, “Settler Colonial Choreography and the Divided Body: Performing Masculinities Through the Switch Dance at a Native American Prison Powwow” (Lecture at University of Michigan Center for World Performance Studies, Ann Arbor, Michigan, February 19, 2020).[↑]

- Toni M. Calasanti and Kathleen F. Slevin, Age Matters: Re-Aligning Feminist Thinking (New York: Routledge, 2007).[↑]

- Sonya Renee Taylor, The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love, 2nd ed. (Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2021).[↑]

- As an example of how a dance studies approach, which analyzes the meanings of yoga postures, can inform yoga studies, see Tria Blu Wakpa, “Hozho Yoga: Indigenous Movements Illuminating Human and More-than-Human Interconnections,” in Practicing Yoga as Resistance: Voices of Color in Search of Freedom, ed. Cara Hagen (London: Routledge, 2021), 133–55.[↑]

- Ananya Chatterjea, Butting Out: Reading Resistive Choreographies Through Works by Jawole Willa Jo Zollar and Chandralekha (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2004); Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).[↑]

- Native Lives Matter (Lakota People’s Law Project, 2015), https://s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/romeroac-stage/uploads/Native-Lives-Matter-PDF.pdf; Susan Wendell, “The Social Construction of Disability,” in The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability (New York: Routledge, 1996), 35–56.[↑]

- Sonya Renee Taylor, The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love, 4.[↑]

- Melanie Yazzie and Cutcha Risling Baldy, “Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and the Politics of Water,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, and Society 7, no. 1 (2018): 1–18.[↑]

- Melanie Yazzie and Cutcha Risling Baldy, “Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and the Politics of Water,” 3; Charlene A. Carruthers, Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018); Robin D.G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002); Michelle LaVigne and Megan V. Nicely, “Curating Dialogue: The Bridge Project’s Radical Movements,” TDR: The Drama Review 62, no. 4 (Winter 2018): 145–53.; Rosemarie A. Roberts, “Radical Movements: Katherine Dunham and Ronald K. Brown Teaching toward Critical Consciousness” (Dissertation, City University of New York, 2005).[↑]

- Michelle LaVigne and Megan V. Nicely, “Curating Dialogue: The Bridge Project’s Radical Movements.”[↑]

- Sonya Renee Taylor, The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love, xvii.[↑]

- Melanie Yazzie and Cutcha Risling Baldy, “Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and the Politics of Water,” 3; Alison C. Novak and Nandini Deshpande, “Effects of Aging on Whole Body and Segmental Control Whole Obstacle Crossing under Impaired Sensory Conditions,” Human Movement Science 35 (June 2014): 121–30.[↑]

- Sabrina Strings and Tria Blu Wakpa, “Rethinking Yoga: Meditations on the Work We Do,” Race and Yoga 1, no. 1 (2016): i–iii.[↑]

- Saku has requested that this article only refer to her by the name “Saku”; the citations that follow will use this name accordingly.[↑]

- Michael Dimock, “Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins” (Pew Research Center, January 17, 2019), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/.[↑]

- Elissa Strauss, “From ‘geriatric Pregnancy’ to ‘35+ Pregnancy’: There’s a Better Way to Talk about Pregnant People,” CNN Health, June 9, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/06/08/health/pregnant-less-offensive-language-wellness/index.html.[↑]

- Thomas DeFrantz and Anita Gonzalez, eds., Black Performance Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014); Yutian Wong, Choreographing Asian America (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2010).[↑]

- Nanako Nakajima and Gabriele Brandstetter, eds., The Aging Body in Dance: A Cross-Cultural Perspective (New York: Routledge, 2017).[↑]

- Misia Denea, interview by the author, June 2, 2021.[↑]

- Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “Shelf Life,” accessed June 22, 2021, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/177862?redirectedFrom=shelf+life#eid23270625.[↑]

- Misia Denea, interview by the author.[↑]

- Miya Shaffer, comment on paper, March 13, 2023.[↑]

- Misia Denea, interview by the author.[↑]

- Mark Singleton, Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).[↑]

- Misia Denea, interview by the author.[↑]

- Jocyl Sacramento, interview by the author, June 3, 2021.[↑]

- Bryan Cave, “Beware of Making Unsubstantiated Anti-Aging Claims” (Lexology, April 7, 2017), https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=735f63cf-3d00-45d7-8777-bc0c8616c04d.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Saku, interview by the author, June 4, 2021.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Misia Denea, interview by the author; Jocyl Sacramento, interview by the author.[↑]

- Andrew Mason, “What’s Wrong with Everyday Lookism?,” Politics, Philosophy & Economics 1, no. 21 (2021): 1–21.[↑]

- Jocyl Sacramento, interview by the author.[↑]

- Misia Denea, interview by the author.[↑]

- Saku, interview by the author. The high turnover rate of teachers at the school is inextricable from structural inequities, which creates many hurdles for low-income, Indigenous students and students of color, such as those who live in South Central Los Angeles. I underscore such structural inequities given that mainstream discourses frequently subordinate, criminalize, and/or blame low-income, Indigenous youth and youth of color.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Jocyl Sacramento, interview by the author.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Sonya Renee Taylor, The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love.[↑]

- Saku, interview by the author; Tria Blu Wakpa, “Decolonizing Yoga? And (Un)Settling Social Justice,” Race and Yoga 3, no. 1 (2018): i–xix; Sheena Sood, “Towards a Critical Embodiment of Decolonizing Yoga,” Race and Yoga 5, no. 1 (2020): 1–12.[↑]

- Saku, interview by the author.[↑]

- Sim Sai Tin and Viroj Wiwanitkit, “Trāṭaka and Cognitive Function,” International Journal of Yoga 8, no. 1 (2015).[↑]

- Saku, interview by the author.[↑]

- Sonya Renee Taylor, The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love.[↑]

- Misia Denea, interview by the author.[↑]

- Jocyl Sacramento, interview by the author.[↑]

- Misia Denea, interview by the author.[↑]

- Jocyl Sacramento, interview by the author.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- “Food Not Bombs: Our Story,” Food Not Bombs (blog), accessed June 28, 2021, http://foodnotbombs.net/new_site/story.php.[↑]

- Saku, interview by the author.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Misia Denea, interview by the author.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Saku, interview by the author.[↑]

- Ibid; Sammy Roth, comment on paper, March 13, 2023.[↑]

- Saku, interview by the author.[↑]

- Misia Denea, interview by the author.[↑]

- Saku, interview by the author.[↑]

- Jocyl Sacramento, interview by the author.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- Ibid.[↑]

- William H. McNeill, Keeping Together in Time: Dance and Drill in Human History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997); Kate Mattingly, comment on paper.[↑]

- Dianne Neumark-Sztainer, Allison W. Watts, and Sarah Rydell, “Yoga and Body Image: How Do Young Adults Practicing Yoga Describe Its Impact on Their Body Image?,” Body Image 27 (December 2018): 156–68.[↑]

- Joanna Lahey, “Age Discrimination in the Workplace Starts as Early as 35,” PBS News Hour, January 15, 2016, sec. Economy, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/age-discrimination-in-the-workplace-starts-as-early-as-35.[↑]

- Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (Princeton University Press, 2021).[↑]

- Sonya Renee Taylor, The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love, xvii.[↑]