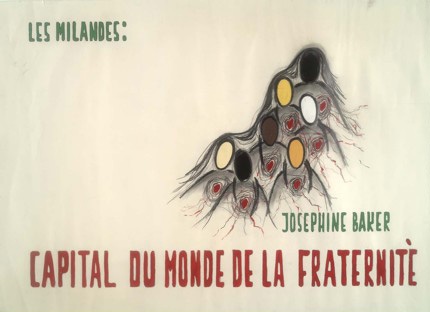

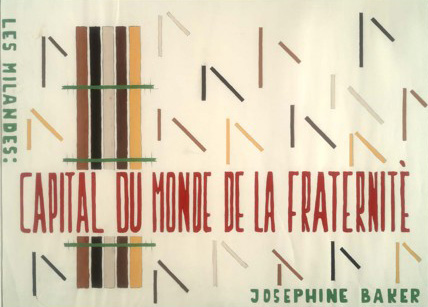

The possibility that Baker’s adoption practices were fueled by a cogent theory, and not simply by enthusiasm alone, comes to light in another of the Scandinavian posters Baker commissioned for Les Milandes [Figure 4]. In this image, the seemingly backward-looking appeal to blood ties in fact offers a striking visual metaphor for adoption. Here, the abstract figures of the children are linked, from heart to heart, by bands of red, a set of prosthetic collective arteries. The blood depicted in the image at once naturalizes the poster’s celebration of fraternity—since the figures all share the same blood—but it also distinguishes this fraternal bond from the functional veins and arteries of each individual body. The shared bloodstream depicted in the image is only the supplemental blood of fraternity uniting the figures; it does not, in other words, represent the mixed blood of miscegenation or, for that matter, of colonial assimilation. It offers instead a visual reminder of the children’s common bond of love, or, to use Baker’s words, their united soul. A related poster design [Figure 5] renders this adoptive graft all the more explicit: in the image, the swatches of color representing the variously pigmented children are bundled together by green bands; rather than invoking the metaphorical sense of blood ties, the green bands figure kinship as the tidy, organizing knots that unite the poster’s abstract bodies. The uniting bands are, of course, painted in the same shade of green as Baker’s name; yet whereas this might seem all too handily to allegorize the calculating agency that guided the formation of Baker’s adoptive family, it also suggests, reciprocally, that Baker’s adoptions could instigate the surrogate bonds of love and “united soul” that would be impossible under existing political and ideological conditions. Indeed, the significance of adoption to this graft of a collective humanity upon irreducible differences of race, religion, and national origin lies precisely in the non-biological and utterly conscious principle of selection involved in such adoptive practices.

Baker’s use of adoption as a symbolic political practice is based, I am suggesting, on what I’d like to call a notion of “adoptive affinities.” The term is derived from Goethe’s notion of elective affinities, which describes chemical properties that force a set of existing chemical bonds to break up in order to make possible another, more necessary set of relations. Goethe’s novel, Elective Affinities, introduces this bit of chemical jargon as an analogy for marital love, emphasizing how a more passionate relationship can dissolve a more conventional one, as if by choice. In Goethe’s case, this affinity is disturbingly anarchic in its power to destroy as well as to create bonds of love, and Baker’s understanding of adoption bears a similar sense of the urgency and voluntarism signified in Goethe’s analogy. “In this forsaking and embracing,” Goethe writes, “in this seeking and flying, we believe we are indeed observing the effects of some higher determination.” 1 On the domestic front, the children of the rainbow tribe were immersed in anecdotes and allegories that strove to naturalize the kinds of pacts a family of surrogates made possible, whether this meant a duck adopting motherless chicks, or a dog nursing an abandoned thirteenth piglet. 2 Narratives aside, though, Baker recognized that the rainbow tribe had to function as a family in order to serve as a symbol for the viability of universal brotherhood. As she wrote in a letter to the producer Stephen Papich in 1964, her children

[h]ave proved that there were no more continents,/ No more obstacles,/ No more problems which could prevent understanding and respect between humans,/ No more excuses that color and religious differences prevent unity. 3

What permitted such a project was, as much in Baker’s case as in Goethe’s novel, the relatively unadulterated social environment of the rural countryside, which prevented, in Baker’s words, the children’s “brotherly education” from being “interrupted by bad spirits.”

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Elective Affinities, trans. James Anthony Froude and R. Dillon Boylan. New York: Frederick Ungar, 1962; 37.[↑]

- See Janot’s anecdote of the dog suckling the thirteenth pig—an anecdote attributed to Jo Bouillon—in Josephine, 208.[↑]

- Ctd. Steven Papich, Remembering Josephine. Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1976.[↑]