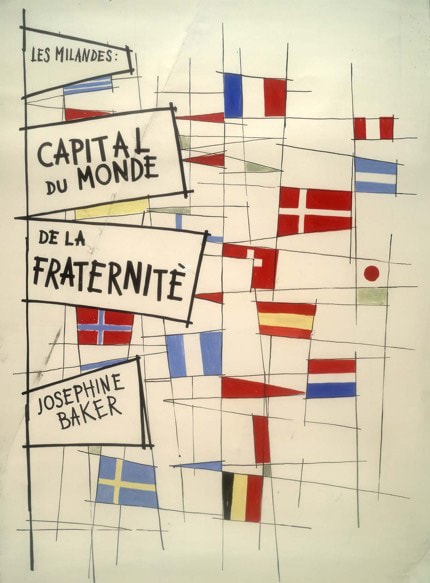

Throughout her postwar career, Baker would tirelessly reiterate the humanistic mission of her family and adopted village in the French southwest. Whereas Garry Davis made his case for global citizenship in explicitly political terms, Baker’s practices of adoption seemed to take place on a more domestic scale. Yet not only did the performer’s massive international celebrity render such domestic practices public, but Baker herself mobilized this celebrity as a means for establishing the rainbow tribe’s symbolic value as what might be considered a depoliticized form of political intervention. As one of a number of poster designs for Les Milandes commissioned in 1958 suggests [Figure 1], Baker promoted the village as a tourist destination in ways that attempted to build Baker’s “world capital of brotherhood” on the order of the United Nations. 1 The design, with its jaunty proliferation of national flags, seems even to borrow the iconography of the U.N. headquarters building in New York, which was completed in 1952. 2 A second poster design [Figure 2], bearing the same slogan, invokes the media attention itself that Baker used to fuel her global village, both financially and politically. A relentless correspondent as well as an oft-interviewed celebrity, Baker’s project relied heavily on her contacts with journalists, photographers, intellectuals, and dignitaries, yet its ideological and political stakes were likewise often abstracted, for the same reason. As Benetta Jules-Rosette has suggested, one of the problems with the design of Les Milandes, and of Baker’s portrayal in the print media, was that her adoptive project could look more like a celebration of universal motherhood—with Baker as a saintly Madonna—than a symbolic embrace of universal brotherhood [Figure 3]. As a result, Baker’s artistic and philanthropic career after the Second World War is often considered a financially doomed and conceptually limited extension of her interwar fame, and her on- and offstage performances as based more on nostalgia than on artistic or political innovation. 3 I would like to propose instead that Baker’s rainbow tribe mobilized both multiracial adoption and Frenchness in an effort to extend, through symbolic means, her civil rights activism of the early 1950s.

One of Baker’s more succinct statements of purpose appears in a letter she wrote in 1959 to her agent, William Taub, in response to his request for details about Les Milandes. For each of the ten children she and Bouillon had adopted by this point, Baker identifies his or her national origin, religion, race, and age. As she writes:

They each are brought up in their own religion so as to prove that religion is an expression of the soul and should unite people instead of separating them and that God is the father of us all.

We adopted these children as an example and a symbol of universal brotherhood and to prove that people of different colors, continents and creeds, can live together in harmony and brotherhood, and that with tolerance, understanding and love there can be a better future for the world.

Every day, our children prove that our theory was right and these children give us profound confidence in the future although the world is confused.

These children are followed closely by special doctors and have been vaccinated against all diseases including polio. 4

Adding that all the children would be tutored in their native languages and would be reintroduced to their native lands by age 12, Baker’s letter emphasizes the extent to which her “rainbow tribe” worked to preserve, rather than to dissolve, the racial and cultural differences among the adoptive children. In certain accounts, this characterization runs into stereotyping, appearing more like the neocolonial small world of Walt Disney than the domestic embodiment of the United Nations. 5 One of the most egregious characterizations of the rainbow tribe’s racial and religious “differences” in such terms is also one of the most prominent: Jo Bouillon’s introduction to the posthumous autobiography of Josephine Baker, which he coauthored, presents the rainbow tribe’s agglomeration of ethnic “types” in memorializing Baker’s death. Remembering Baker as “a woman of a hundred faces,” Bouillon writes:

These faces rose before me as I traveled through the darkness to Josephine’s side. And with them came the beloved faces of the children. Akio, almond-eyed, sensitive, serious; Jarri, with his Nordic fairness and stamina, Jean-Claude, our blond Frenchman, blessed with an innate equilibrium; Mara, a full-blooded Indian, who hoped to become a doctor because they are lacking in his native Venezuela; Janot, the Japanese, whose love of plants and flowers points toward a career in horticulture; Brahim and Marianne, found abandoned under a bush in the midst of the Algerian war, he the son of an Arab, she a colonial’s granddaughter; dusky Koffi from Abidjan, with his purity of spirit […] 6

Bouillon’s litany continues, closing with an image of how the children’s’ faces were “overshadowed by images of Josephine, friend of the rich and poor, the unknown and famous.” Not only does Bouillon, throughout his contributions to Baker’s autobiography, portray the children as appendages of the dancer’s personality, but the sentimentalized racial essentialism of Bouillon’s taxonomy also overshadows the more nuanced ways in which Baker conceptualized the rainbow tribe.

- The posters, which now form part of the Josephine Baker collection at Emory University’s Special Collections Library, were designed by the Scandinavian artists Inger Kihlman and Leif Kristensen.[↑]

- Notably, there is no flag of the U.S. in the poster’s composition. While hardly an adamant form of political expression, this exclusion suggests the extent to which Baker’s internationalist project was, however neutrally it voiced its pluralism, tied to an implicit rejection of U.S. domestic and international policy.[↑]

- For treatments of this notion see, for instance, Benetta Jules-Rosette, Josephine Baker in Art and Life: The Icon and the Image. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2007; Phyllis Rose, Jazz Cleopatra: Josephine Baker in Her Time. New York: Doubleday, 1989.[↑]

- Letter to William Taub, Emory University Special Collections.[↑]

- Josephine Baker and Jo Bouillon, Josephine. Trans. Mariana Fitzpatrick. New York, Harper and Row, 1977, ix-x.[↑]

- Josephine Baker and Jo Bouillon, Josephine. Trans. Mariana Fitzpatrick. New York, Harper and Row, 1977, ix-x.[↑]