Albuquerque, New Mexico is a growing Southwestern city, home to a diversity of cultures in a colorful, vibrant setting. It is also home to a unique non-profit organization, developed over the last 37 years to serve at-risk children and families. While directly serving a specific community, systems and policies have emerged that have resulted in cutting-edge practices for those who frequently have no voice at policy tables.

PB&J Family Services, Inc. (affectionately known as Peanut Butter and Jelly) was founded in 1972 in Albuquerque’s rural Southwest valley in response to a scarcity of services for young children. Its first target population was children of mothers being treated at the county mental health center. It then grew to inform child welfare practices more widely in the Albuquerque area.

I write this article as PB&J’s co-founder and Executive Director emeritus, having served as its ED for 35 years. PB&J defines its mission to serve at-risk children to grow to their full potential within nurturing families in a supportive community. Over the years, the effort of helping our families to become more nurturing has faced significant challenges. Creating supportive communities and families has meant incorporating the spaces of prisons and jails into family and community life—an effort with countless barriers. The growth of PB&J has been, in every instance, a response to the needs of children and families that have emerged in a changing society.

Although PB&J now provides services for nearly two thousand highly challenged lives, its beginnings were rooted within a handful of mothers in the early 1970s when I was employed at the University of New Mexico’s mental health center. With interest, I observed these young women coming in for treatment. They’d sit around a large table doing arts and crafts as a nurse walked around the table injecting each woman with a psychotropic medication. We used Prolixin at the time, which was thought to be an effective chemical combatant for clinical depression. After the group activities, the women were given a vial of Thorazine tablets to offset the side effects of the Prolixin, and we wouldn’t see them until their scheduled treatment the following week.

I wondered, who are these women? Are they parents? Who are they going home to? Whose lives do they affect? Who affects theirs? In those days, we didn’t have public transportation in Albuquerque’s rural valley areas, so I began asking the women if they wanted rides home. One by one they accepted, and, as I left them at their front doors, I realized that every woman was a parent of very young children.

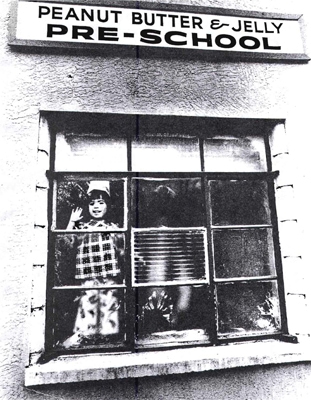

Having been a teacher, I decided to start a small school for these kids in order to get them out of the dark environment in which they lived, and provide some stimulation and learning. With my friend and co-worker, a child development associate named Christine Ruiz, we located donated space in a storage room, cleaned it up, received donated crayons, paper, puzzles, tables, chairs, and snacks, borrowed a bus every morning from the mental health center, and off I’d go around town picking up children to take them to their new school.

The children’s response was nothing short of amazing. These quiet, withdrawn children became animated and active. They danced, sang, and played. As time passed, however, unexpected and unintended results occurred. Children began to show signs of significant physical abuse.