What I will do is read a little from the memoir and then offer some reflections on writing memoirs. I read first of all, from the very beginning of the book:

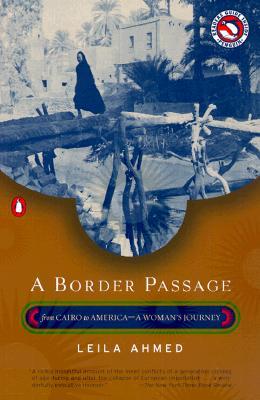

(The following excerpts are from A Border Passage: Cairo to America – A Woman’s Journey by Leila Ahmed. Copyright © 1999 Leila Ahmed. Used by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. All rights reserved.)

“It was as if there were to life itself a quality of music, in that time, the era of my childhood, and in that place, the remote edge of Cairo. There, the city petered out into a scattering of villas leading into tranquil country fields. On the other side of the house was the profound, unsurpassable quiet of the desert.

There was, to begin with, always the sound, sometimes no more than a mere breath, of the wind in the trees, each variety of tree having its own music, its own way of conversing. I knew them all like friends, although none more intimately than the trees on either side of my corner bedroom. On one side was the silky, barely-perceptible breath of a mimosa, which, when the wind grew strong, would scratch lightly at the shutters of the window facing the front of the house, looking out onto the garden. On the other side was the dry, faintly-rattling shuffle of the long-leaved eucalyptus that stood on the street side. On hot nights, the street lamp cast the shadows of the twirling eucalyptus leaves onto my bedroom wall – my own secret cinema. I would fall asleep watching those dancing shadows, imagining to myself that I saw a house and people in them, and telling myself stories about their lives.

I loved too, the patterns of light cast by leaves on the earth, and I loved being in them, under them. The intricate, gently-shifting patterns the flame tree cast where the path widened towards the garden gate, fading and growing strong again as a cloud passed, could hold me still for long moments.

Almost everything, then, seemed to have its own beat, its own lilt: sounds that distilled the sweetness of being, others that made audible its terrors, and sounds for everything between. The cascading cry of a karawan, a bird I heard but never saw, came only in the dusk – its long, melancholy call descending down the scale was like the pure expression of lament at the fall of things, all the endings that the end of light presaged.

And sometimes, in the earliest morning, there would be the sound of the reed piper playing his pipe as he walked past our house. A simple, lovely sound, when he was gone it would feel as if something of infinite sweetness had momentarily graced one’s life and then faded irretrievably away.

Years later, I’d discover that in Sufi poetry this music of the reed is the quintessential music of loss and I’d feel, learning this, that I’d always known this to be so. In the poetry of Rumi, the classic poet of Sufism, the song of the reed is the metaphor for our human condition, haunted as we so often are by a vague sense of longing and nostalgia, but nostalgia for we know not quite what. Cut from its bed and fashioned into a pipe, the reed forever laments the living earth it once knew, crying out whenever life is breathed into it, its ache and yearning and loss. We, too, live our lives haunted by loss, we too, says Rumi, remember a condition of completeness that we once knew but have forgotten we ever knew. The song of the reed and the music that haunts our lives is the music of loss – of loss and of remembrance.”

Next I’m going to read a short passage from a later chapter of an encounter between my mother and myself:

“Most commonly, Mother spent her afternoon reading. That’s how we remember her: reading. Sitting, freshly bathed, on the chaise lounge in her bedroom, wearing fresh cotton clothes, clothes with the sweet smell of cotton dried in the sun, the air blowing through them. Behind her, the garden. French windows open, curtains lightly billowing. A book in her hand, a cup of Turkish coffee on the table beside her.

Two moments in particular live for me. One of these was on just such an afternoon, the air lightly stirring the curtains, the sound of running water drifting in. She was on the chaise lounge, a book in her hand or perhaps lying face down beside her because I had come in and she had stopped reading and looked up, waiting to hear me speak, a cigarette in her hand. I’d wandered into her room, I don’t know why. We must have had some conversation and I must have said – I was probably about 15 at the time – that I wanted to be a writer. I don’t remember saying this, nor can I now imagine why I would have said that to her: I wasn’t wont, in my memory of our relationship, to speak to her of my secret desires. Still, I must have done so because I remember her looking up at me and saying, speaking with animation, that she too would have liked to have been a writer. It was too late for her now, she said. But sometimes she thought about her life and how interesting it had been, and wished she could write it all. Maybe I could write it for her, she said. Maybe she could tell me the story of her life and I could write it. ‘I’d tell it to you and you could write it,’ she said. She spoke enthusiastically, eagerly, looking at me.

I was 15. Like many girls at that age, I was sure of one thing – I didn’t want to be like my mother. I was sure I wasn’t like her and I wouldn’t grow up to be like her. I didn’t want to think that we were alike in anything, let alone, in our deepest desires.

And so of course I wasn’t at all taken with the idea. Rather, anxious to distance my own desires from hers, I thought to myself that what she dreamed of doing, writing a memoir, telling the story of her life, wasn’t at all what I wanted to do. After all, there was nothing in the least interesting about writing the story of one’s life.”