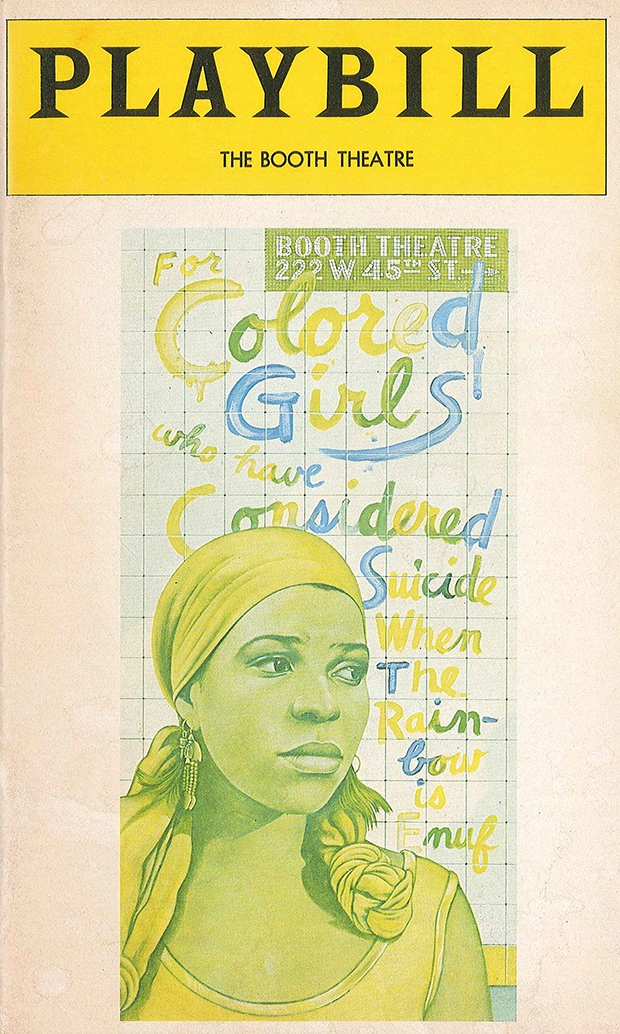

Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf opens with a poem entitled “dark phrases.” The first stanza reads:

dark phrases of womanhood

of never havin been a girl

half-notes scattered

without rhythm/ no tune

distraught laughter fallin

over a black girl’s shoulder

it’s funny/ it’s hysterical

the melody-less-ness of her dance

don’t tell nobody don’t tell a soul

she’s dancin on beer cans & shingles 1

Shange’s for colored girls produces and idealizes black feminist collectivity from the opening stanza to the final “laying on of hands.” Implicitly, if nationalist rhetoric and patriotic action aspire and move toward a more perfect union, that union remains an ideal that is always set at a distance from the lived experience of the citizen. for colored girls presents an aspirational black feminist collectivity as an alternative to the heteronormative domesticity that is the primary organizing social logic of the state. As an ideal, the black feminist collective destabilizes state fantasies including the American dream. Drama seeks to imagine a world that may be inspired by the mundane, but is not bound by reality. Therefore drama participates in crafting national, communal, personal, and social ideals. Ideals are important precisely because they are aspirational—because they provide a vision of worlds we wish to inhabit and possibilities worth fighting to realize.

for colored girls cultivates black feminist collectivity through the form of the choreopoem, which integrates poetics and scripted movement. Robin Bernstein has argued persuasively for the way objects as things inspire relationships with individuals, prescribing a set of actions, scripting behavior. 2 Bernstein suggests that objects create social cues that motivate certain actions from individuals: red lights encourage drivers to stop their cars, wailing alarm clocks provoke individuals to wake from their slumber, beeping iPhones prompt users to check their messages. Using thing theory, Bernstein explains that in the moment when the object inspires action, it transforms from an object into a thing and blurs the strict hierarchy between humans and objects. Bernstein’s formulation of scriptive things uses the dramatic text—the script—as its ideal object-turned-thing, calling attention to the way the dramatic text participates in encouraging social relations. I would further suggest that the imaginary and sometimes visionary process that the dramatic text scripts differentiates artistic endeavors from quotidian ones. This means that the script as a thing not only calls forth social relations but imagines them as well.

In this essay, I explain how scripted actions create fantasies and attachments that sustain intellectual, political, and social projects. Shange’s for colored girls presents and establishes alternative socialities for theater practitioners and audiences as well as students and scholars reading and studying the play in classrooms and intellectual communities. My analysis focuses on the way storytelling through poetics becomes intertwined with the touch in the first and final scenes of the choreopoem. The touching that opens and closes the drama creates links across and between the individual poems, enabling individual innovation and expression within collectivity. The touching in for colored girls imagines a nonsexual but yet still intimate mode of racialized communal formation.

In the choreopoem, bodies become conduits for producing social relationships. Instead of emerging as props in the social drama, the women, through touch, express feeling, cultivate community, confront pain, and engage in play and pleasure. The movements that facilitate touch work against the demonization of black women because of their bodily difference. Through the touching bodies, the women demonstrate the humanity of black women, disrupting subject-object relations by having the body express itself. Moreover, the structuring of for colored girls through touch purposefully engages with the black feminist calls for intersectionalist approaches to literary and cultural studies that emerged during the black women writers’ renaissance of the late-twentieth century because the choreopoem as a formal innovation demands an understanding of how intimate contact produces race. While Bernstein’s essay “Dances with Things” calls attention to how the enlivened object as thing may create racist interactions, I am suggesting that Shange’s dramatic text functions as a liberatory object by drawing subjects formerly known as objects into intimate relationships as humans.

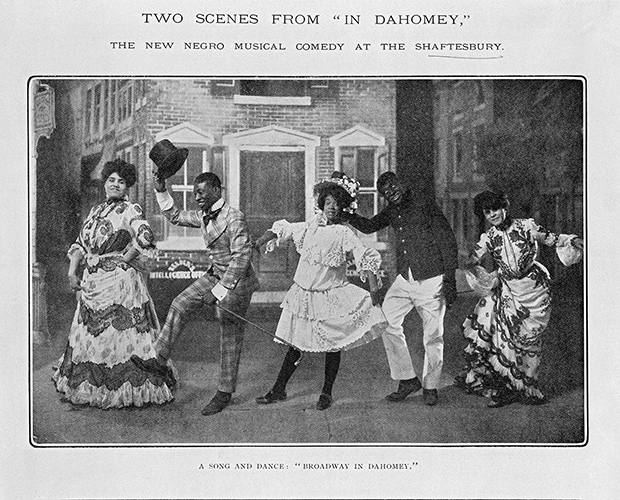

As Michael Awkward’s thoughtful analysis of the opening lines of for colored girls explains, the dramatic work foregrounds “the struggle to make articulate a heretofore repressed and silenced black female’s story and voice. Against a backdrop of patently stereotypic misreadings of black women (‘are we ghouls?/children of horror?/the joke?/…are we animals? Have we gone crazy?”), Shange’s woman in brown plaintively cries out for accurate, revelatory representations of Afro-America women’s lives.” 3 Awkward draws attention to the discursive designations that shape black women’s social roles in the United States. Alongside the call for storytelling that will narrate a social drama that does not demonize black women, lady in brown describes the distorted movements that accompany the mischaracterizations, “half-notes scattered / without rhythm/ no tune / distraught laughter fallin / over a black girl’s shoulder / it’s funny / it’s hysterical / the melody-less-ness of her dance / don’t tell nobody don’t tell a soul / she’s dancin on beer cans & shingles.” 4 The imagery in the opening lines suggests that colored girls diffuse pain with laughter, dance, and secrecy, which, considering the hostile environment, is only partially effective in producing the joy of dancing. At the same time, the imagery calls attention to a history of black dancing in the midst of circumstances that range from unfriendly to dangerous. From the plantation to the Broadway stage, black dancers have co-opted spaces to perform and transform environmental dissonance into syncopation.

Black women often provide the supplemental, ghostly, and unappreciated labor necessary to maintain the nation-state as an ideal and lived reality. The controversy over Beyoncé Knowles lip-synching the national anthem at the second presidential inauguration of Barack Obama recalls Farah Jasmine Griffin’s analysis in “When Malindy Sings: A Meditation on Black Women’s Vocality.” Griffin asserts, “Since Marian Anderson, the voice and the spectacle of the singing black woman often has been used to suggest a peacefully interracial version of America. In the majority of these spectacles there is the suggestion that the black woman singer pulls together and helps to heal national rifts. This singing spectacle offers an alternative vision of a more inclusive America.” 6 When Beyoncé stood before the podium on January 21, 2013, to sing the national anthem she became a part of “the voice and the spectacle of the singing black woman.” Beyoncé’s choice not to lay her body on the line—not to risk damaging her vocal chords by singing in the cold—in the service of nation-building caused a flurry of speculation and criticism as it called attention to a particular national intimacy with black women’s bodies. 7 The events that followed, including the press conference where Knowles clarified her actions and sang the anthem a cappella, reinforced the notion that black women must pay a national debt and therefore owe the populace an explanation for the deployment of their bodies. The persistent questioning of her choice may be understood as a demand for her ongoing excess labor in nation-building. “A figure,” according to Griffin, “that serves the unit, who heals and nurtures it but has no rights or privileges within it—more mammy than mother.” 8

The designation of black women as social outcasts, more mammies than mothers, provides insight into what Lauren Berlant calls the cruel optimism that results from black women investing in institutions—the patriarchal family and nation-state—that offer access to limited measures of national belonging, but only in the midst of danger and pain (dancing on beer cans and shingles). Berlant explains, “A relation of cruel optimism exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing.” 9 The object, whether the patriarchal family or the neoliberal state, is desirable by definition and exists as a site of longing in advance of late-twentieth-century black women’s subject formation. The first two lines of for colored girls (“dark phrases of womanhood / of never havin been a girl”) reveal how subject positions emerge in relationship to preexisting social configurations—values, systems of desire, and structures of disenfranchisement. Therefore, establishing an alternative object of desire not only requires an act of will but it also entails restructuring desire itself through word and deed.

While Berlant offers a rubric for understanding the precarity of the late-twentieth century and the waning appeal of what she calls “the good life,” one may suggest that at least since Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun appeared on the Great White Way in 1959, the United States has been depicted as a site of deferred dreaming for black folks as a result of the state’s continual deferment of equal rights. The state’s false promise of equality places black folks in a perpetual state of longing that calls attention to the necessity of creating alternative sites of belonging. One may read the alternative ideal of feminist collectivity that for colored girls provides in relationship to the tenuous hold of the twenty-first century of American exceptionalism, which seems to be losing its grip everywhere. At the same time, one may also understand Shange’s play as a response to the call for dreaming that A Raisin in the Sun issued in 1959. for colored girls sings a black girl’s song in a way that interrupts deferral and prevents the dream from drying up like a raisin. The choreopoem creates collectivity based on the intertwining of bodies in space and words in rhythm in order to counter the displacement and dehumanization of black women’s voice, bodies, and experiences.

- Ntozake Shange, for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf (New York: Scribner, 2010).[↑]

- Robin Bernstein, “Dances with Things: Material Culture and the Performance of Race,” Social Text 27.4 (2009): 67-94.[↑]

- Michael Awkward, Inspiriting Influences: Tradition, Revision, and Afro-American Women’s Novels (New York: Columbia UP, 1989), 1-2.[↑]

- Shange, for colored girls 2010: 17.[↑]

- Daphne Brooks, Jayna Brown, and I provide histories of the cakewalk dance that demonstrate how the dance’s deployment shifted the relationship between the performers and the space in which they performed and opened up new sites of performance for black dancers. See Daphne Brooks, Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances Freedom, 1850-1910 (Durham: Duke UP, 2006) ch. 4; Jayna Brown, Babylon Girls: Black Women Performers and the Shaping of the Modern (Durham: Duke UP, 2008) ch.4; and Soyica Diggs Colbert, The African American Theatrical Body: Reception, Performance and the Stage (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2011) ch. 3.[↑]

- Farah Jasmine Griffin, “When Malindy Sings: A Meditation on Black Women’s Vocality,” Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies eds. Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin (New York: Columbia UP, 2004) 102-125, 104.[↑]

- A similar expression of intimacy occurred in the regulatory responses to Janet Jackson’s “wardrobe malfunction” at the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show. For a cogent reading of the media response to Jackson’s exposed breast see chapter three of Nicole Fleetwood’s Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality and Blackness (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2011).[↑]

- Griffin, “When Malindy Sings,” 104.[↑]

- Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke UP, 2011) 2.[↑]