Interference Archive in Brooklyn, New York, is a volunteer-run, collectively operated space that explores the relationship between cultural production and social movements. The Archive’s collections are comprised of material culture produced and disseminated through social movements. This exhibit has been put together to present visual culture that illustrates the nonprofit industrial complex (NPIC); it represents a small fraction of the material culture housed at Interference Archive.

We didn’t initially realize in how many different directions our conversation about the NPIC would go. We wondered: do we start with U.S. education, adjunct and student organizing, or The Peoples Climate March? How do we consider U.S. foreign aid and non-government agencies together alongside domestic institutional structures like museums? While looking through our collections, we noted that the NPIC is not always depicted overtly, but is represented by indirect allusion to the larger context through which nonprofits exist.

Taking a broad look at the effects of the NPIC on our work, lives, and relationships, we widened our vantage to focus on how nonprofits and non-government agencies work in tandem with capitalism and in competition for resources. We centered discussion on the ramifications of the NPIC’s allocation of power. For example, funded nonprofit organizations can become so concentrated on staying intact as an organization that they lose sight of their original mission. This is especially concerning within the realm of community activism. Across the board, this inward focus can fracture the work of any nonprofit.

While much of our discussion aligns with the conversations in The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex, edited by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence, some things in the NPIC have changed since its publication. Alarmingly, we began to notice within the NPIC a strong adoption of a corporate business model that requires continual “expansion” to achieve validation. Here we see aggravated societal division rather than solutions to inequality coming from today’s NPIC. We hope our exhibit illustrates some of these points.

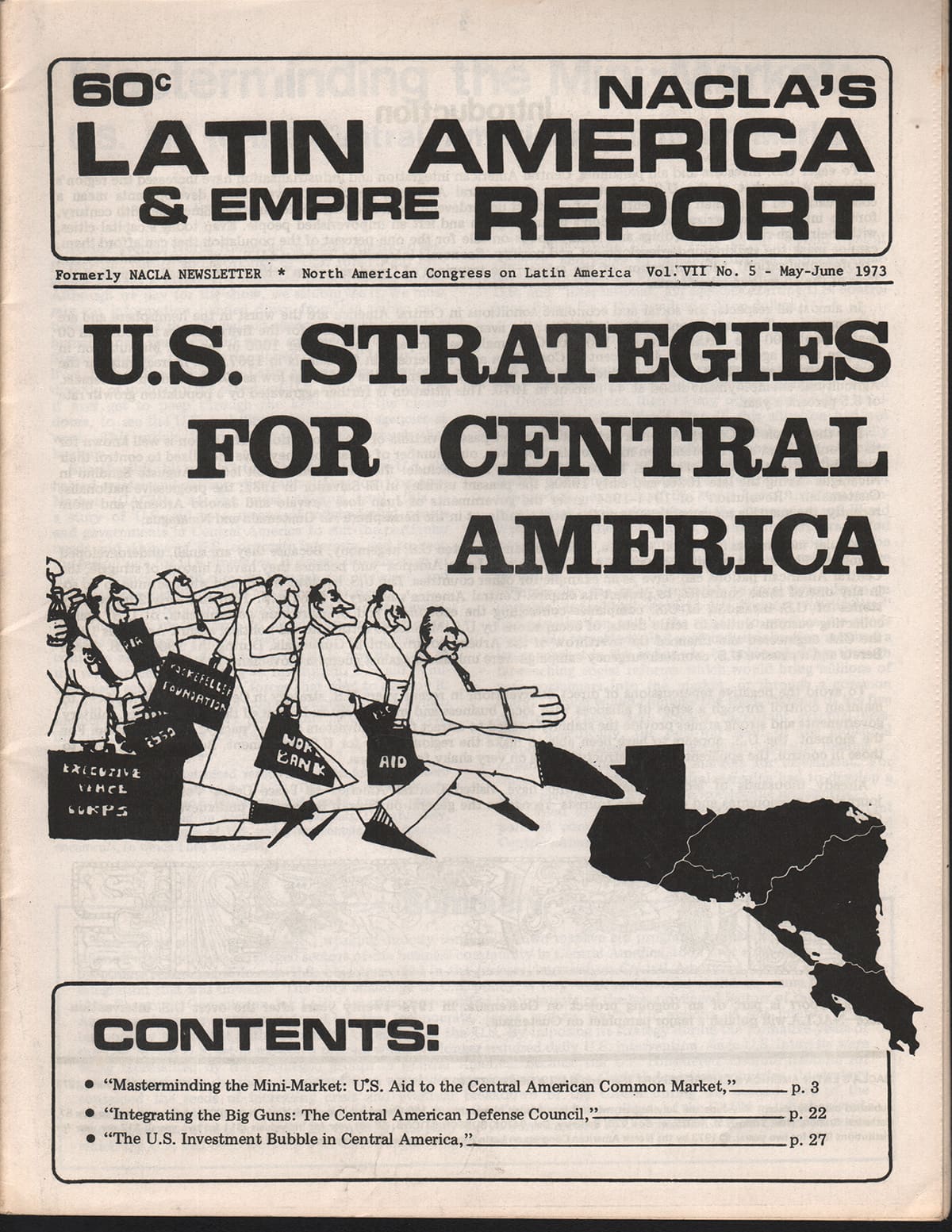

Image 1: NACLA’s Latin America and Empire Report, May-June 1973

The cover of this publication presents corporate interest marching into Central America under the auspice of International Development. Written on briefcases of men in suits are the words AID, World bank, Executive Peace Corps, Rockefeller Foundation. In an accompanying article, North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) outlines the problem: “The implications of this story go far beyond Central America, and apply to hundreds of institutions in under-developed countries, which have felt the heavy hand of the U.S. and “international” aid agencies exerting U.S. control in exchange for a few hundred million dollars.” (NACLA, 1973, 3)

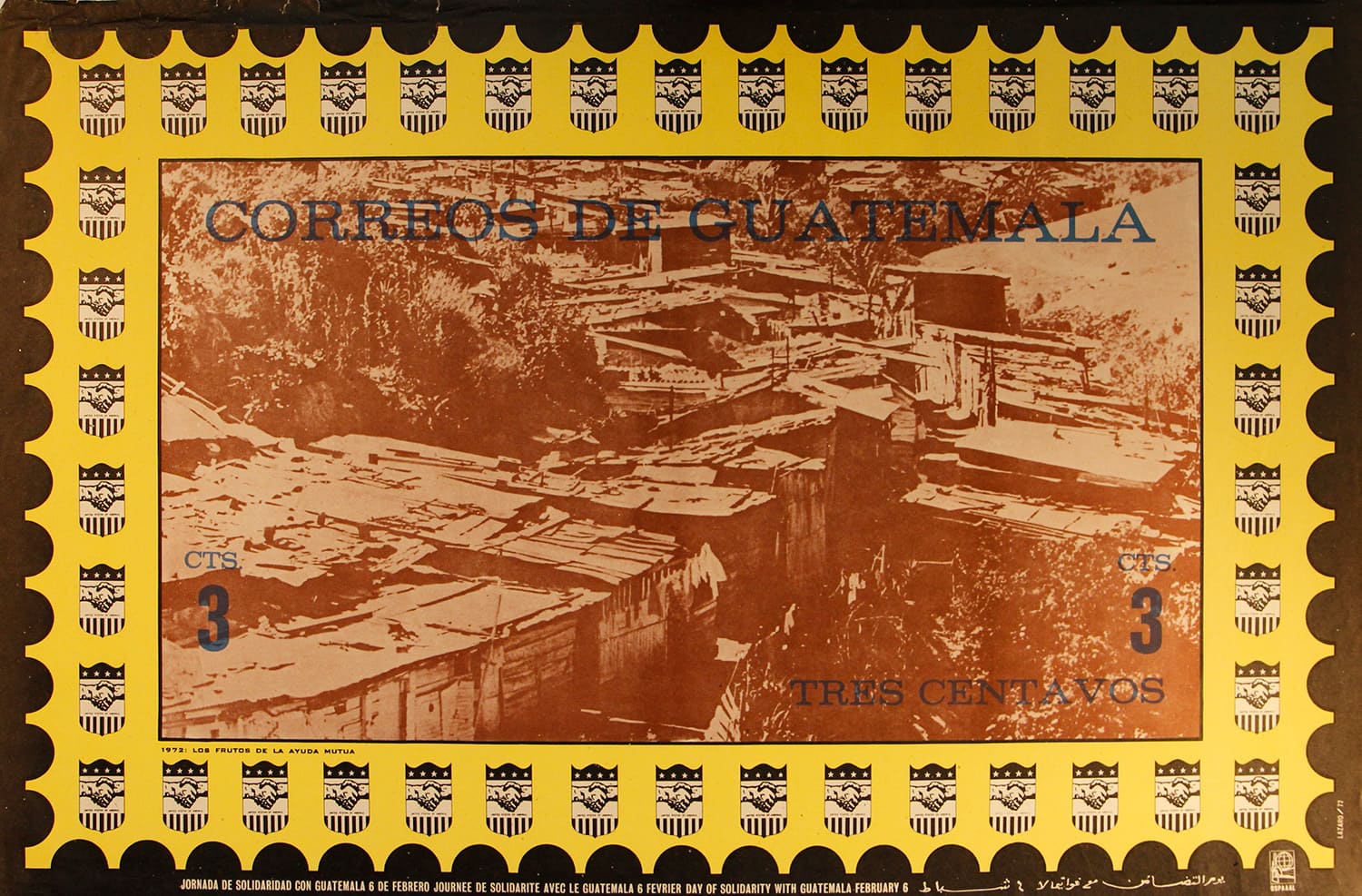

Image 2: Organization of Solidarity of the People’s of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL), Guatemala, 1972

Cuba’s OSPAAAL existed to create graphic design material in solidarity with anti-imperialist movements worldwide. However, this poster from 1972 takes OSPAAAL’s message one step further, by relating USAID iconography and international development policy with imperialism.

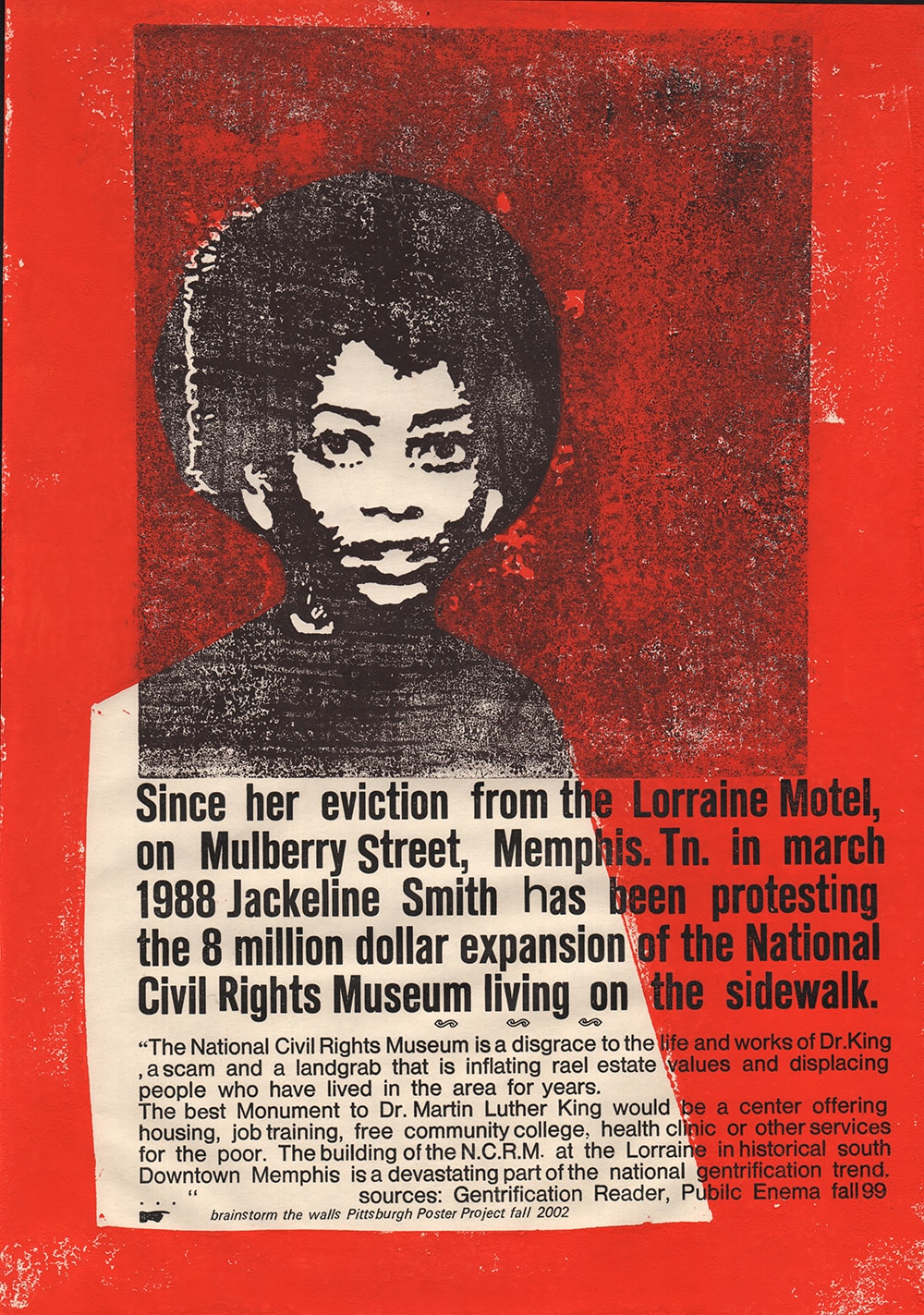

Image 3: Jacqueline Smith and the Lorraine Hotel Eviction for the National Civil Rights Museum (brainstorm the walls Pittsburgh Poster Project, Fall 2002)

Large-scale development of the National Civil Rights Museum, a non-profit organization concerned with civil rights, both displaced and criminalized Jacqueline Smith, a resident of and employee at the Lorraine Hotel when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was shot. She has been calling attention to gentrification and segregation by protesting on this site for over 20 years.

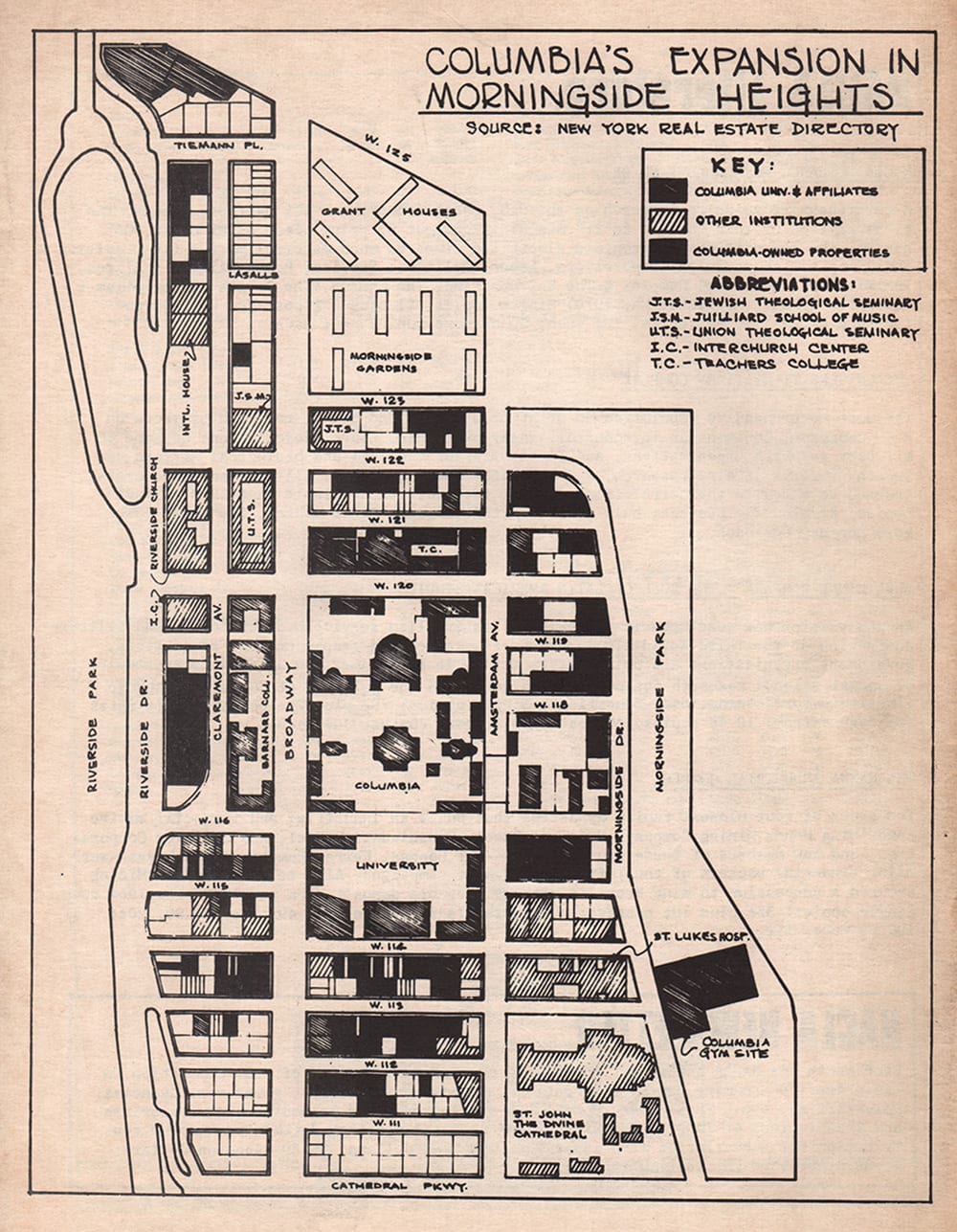

Image 4: Columbia University Expansion Map, 1968

Columbia University is a top-ranked non-profit education institution; this map from 1968 renders the area of Columbia University’s expansion plans, which resulted in large-scale displacement of low- and middle-income neighborhoods. Students occupied several campus buildings in protest, and community organizations SNCC and CORE marched through campus in April of 1968. Protests staved off development for 42 years until 2010 when Columbia won eminent domain.

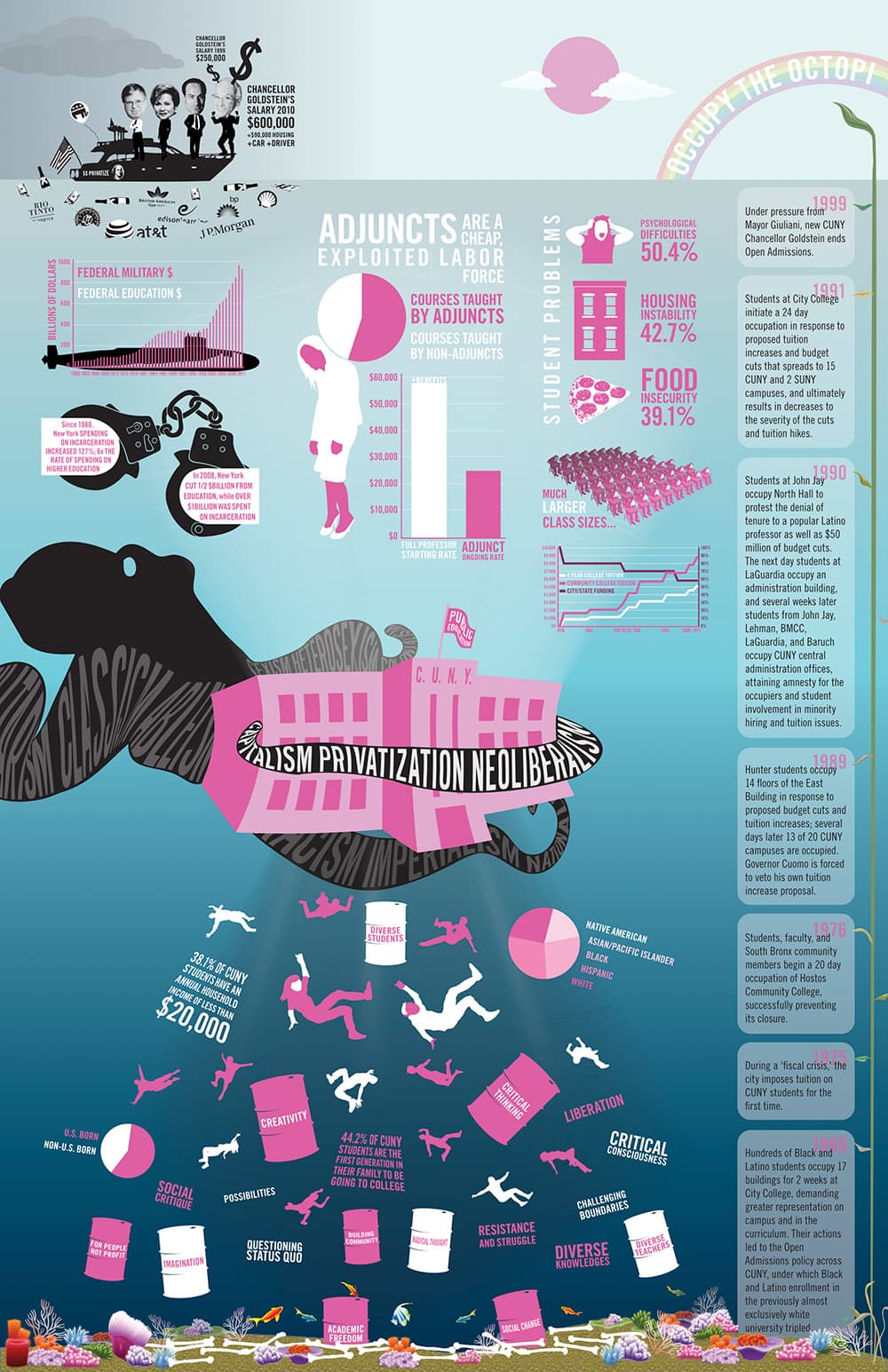

Image 5: Occupy the Octopi (CUNY) poster by Rachel Liebert and Daniel Ward

Universities, both public and private, are a space where the affect of the NPIC is very apparent. We see this in the way funds are allocated, in how salaries are determined, and tuition prices are set, as well as in who is invited into the institution by faculty/staff hiring and student acceptance.

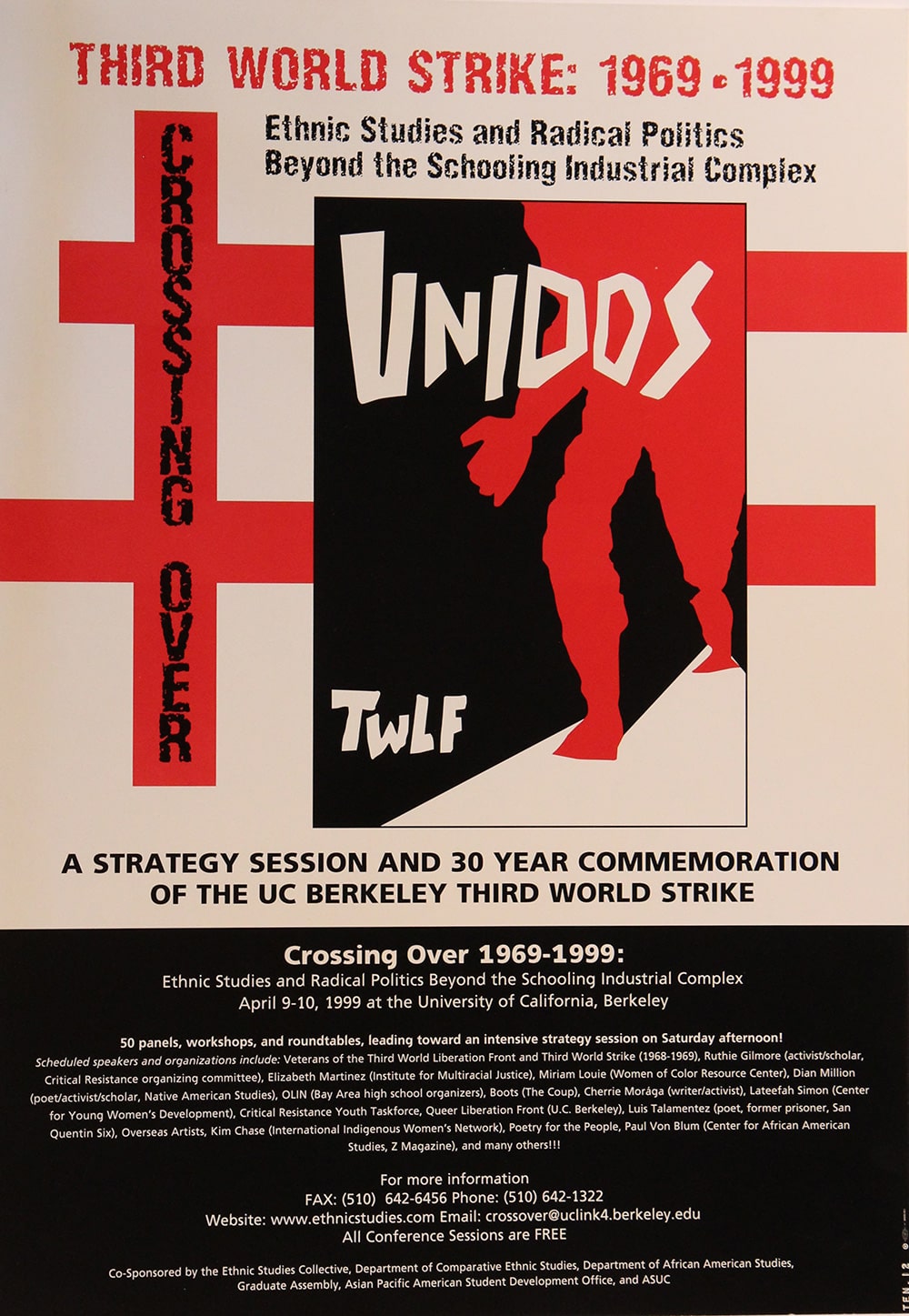

Image 6: Ethnic Studies and Radical Politics poster, 1999

This poster was made for the 30-year anniversary of the 1969 student strike at University of California Berkeley. African American, Asian American, Chicano and Native American students organized a group known as the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF), which led student strikes and demanded the establishment departments focused on Asian American, African American, Chicano and Native American Studies. Over 150 students were arrested, and National Guard troops were called in. This strike resulted in the establishment of the Ethnic Studies program at UC Berkeley.

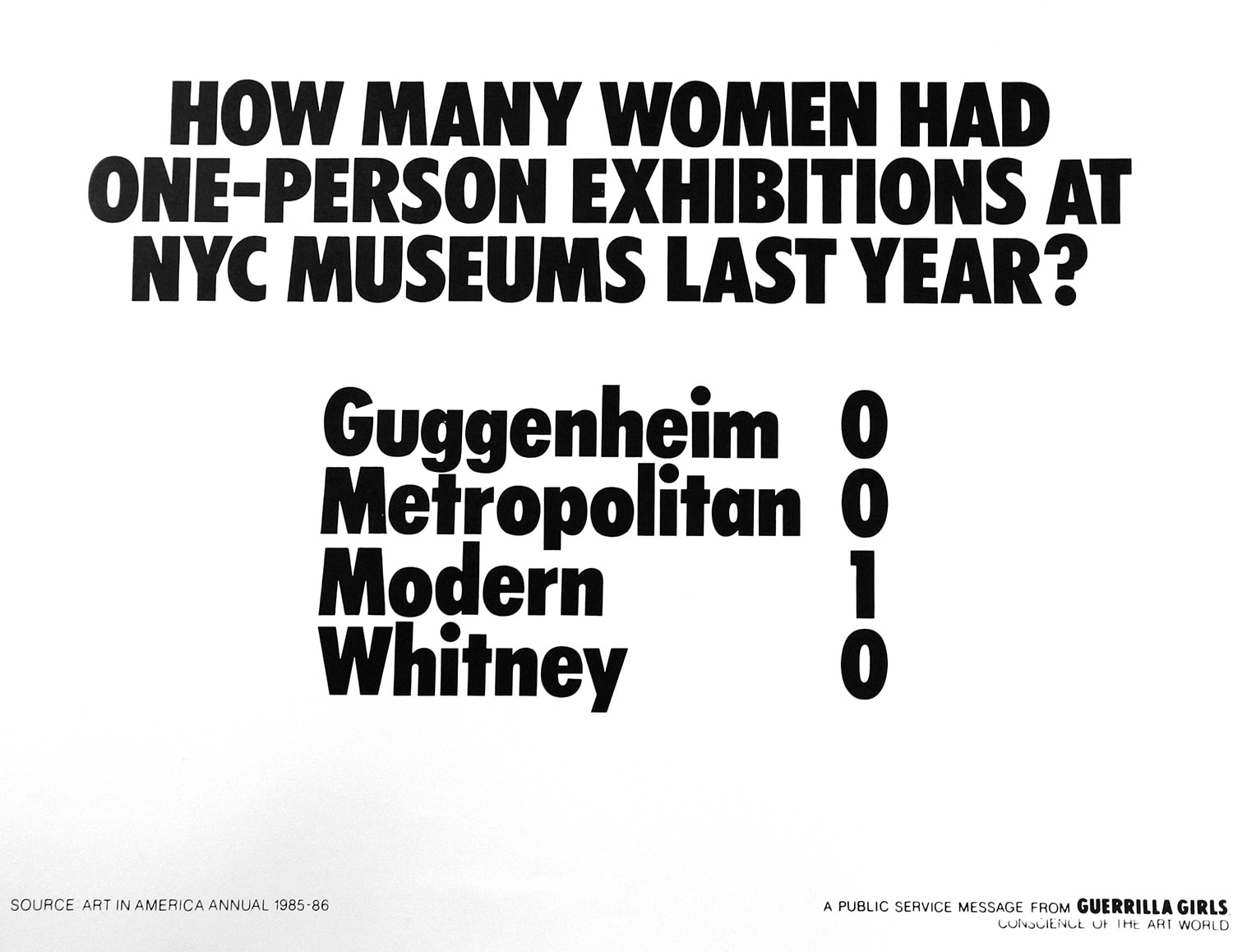

Image 7: Guerrilla Girls poster, 1985

Non-profits have long been critiqued for maintaining normative class, gender, and racial segregation. The Guerrilla Girls specifically targeted the lack of representation of women and artists of color in large non-profit art institutions.

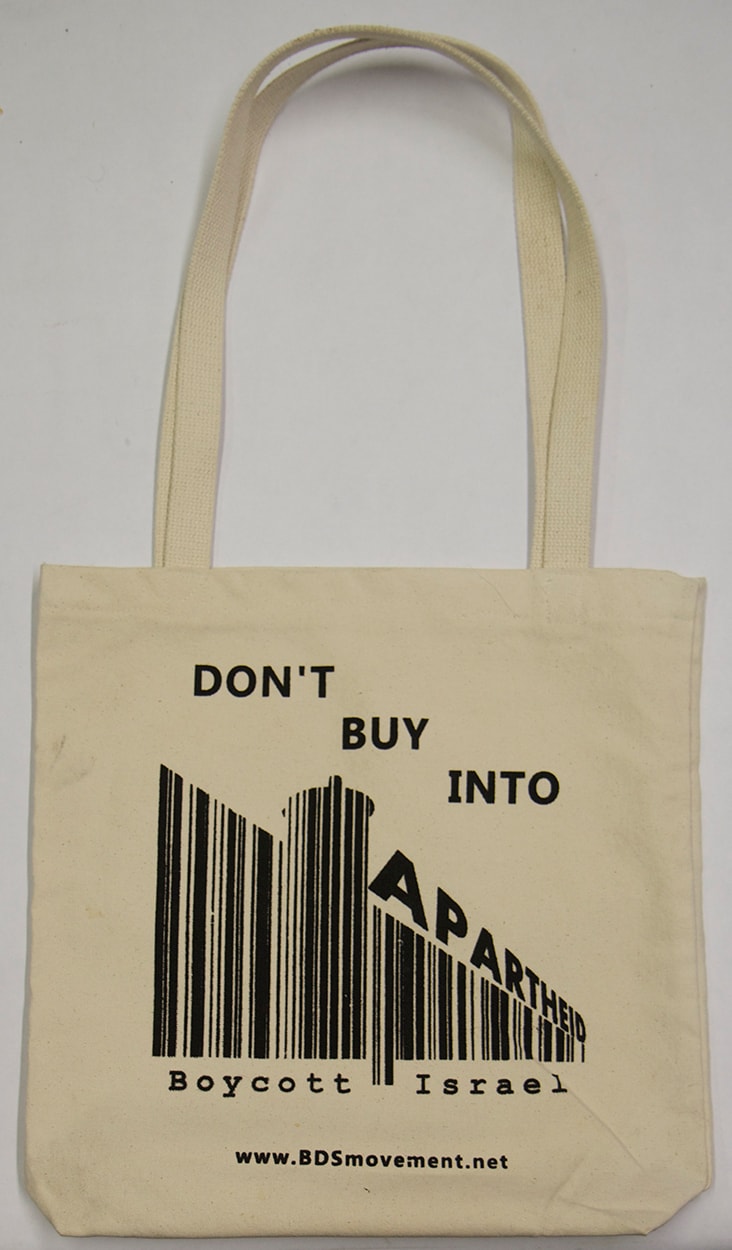

Image 8: “Don’t buy into Apartheid” (Boycott Divestment and Sanctions) totebag

Social movements almost always inspire visual representation from artists. In this work of art, Sam Empress illustrates the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. The connection between the AIC and BDS is covered thoroughly in this issue of S&F Online in “The Academic Boycott of Israel.”

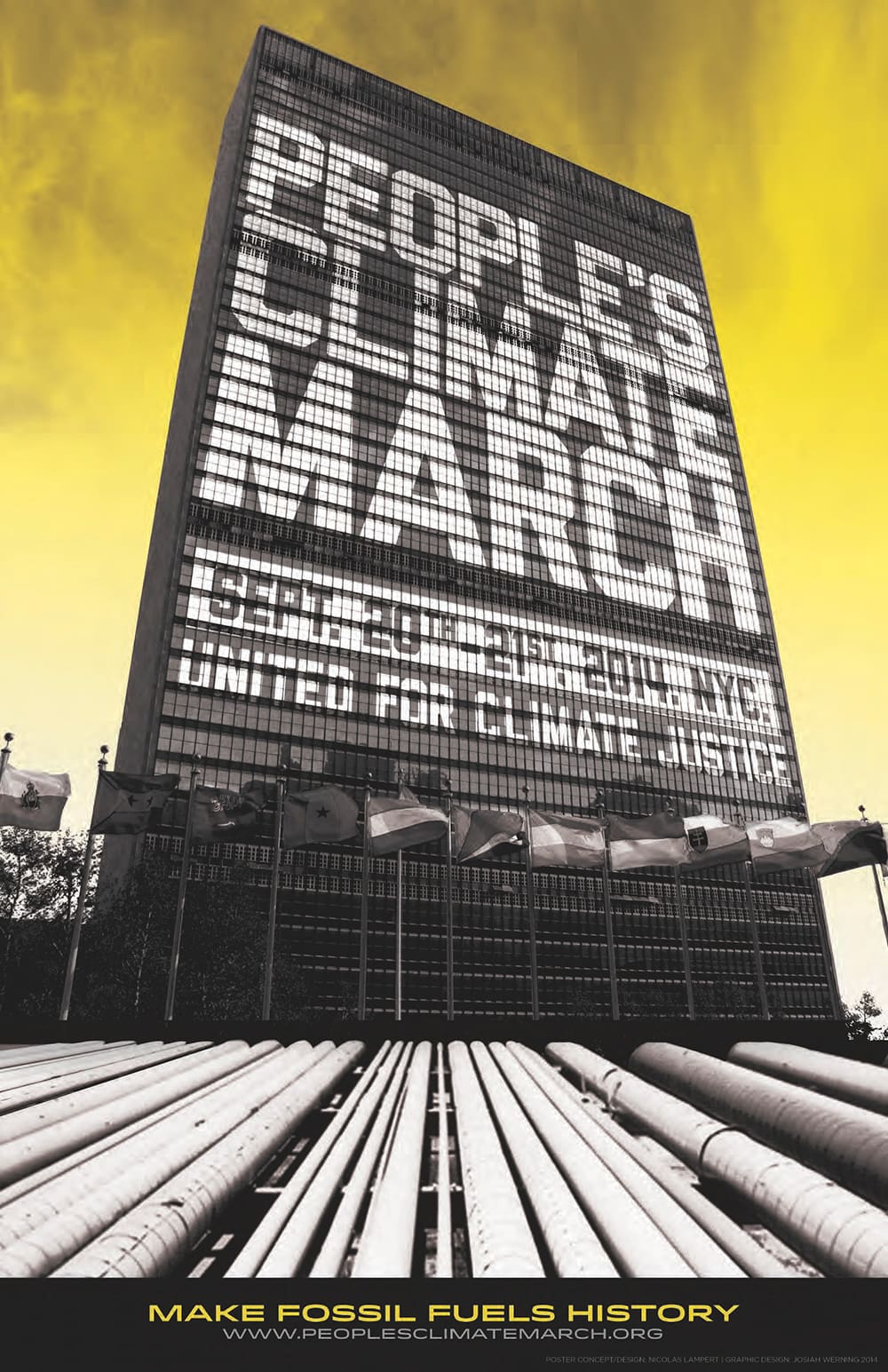

Image 9: People Climate March Billboard poster, 2014

This image illustrates the linking of corporate sponsorship and the NPIC, with imagery that depicts the scope of media outreach that was organized for this action. For the NYC March in September 21, 2014, as an organization, The Peoples Climate March had over 1500 sponsors, and over 400,000 people came out to March in NYC. The Peoples Climate March represents large-scale action supported by corporate sponsorship and business-like advertising.

Conclusion

As many of the authors from The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-profit Industrial Complex have warned, the non-profitization of activism has a tendency to drastically change organizations, potentially losing their radical creative possibilities for change, by moving the focus to organizational stability and growth of the nonprofit itself. These images force us to consider how social movements have been incorporated in both the NPIC and the for-profit sphere. Here the language and aesthetic of social change becomes an “entrepreneurial” opportunity. This begs the question: what is next for the Non-profit Industrial Complex?