“Jovita Rivera said a doctor told her she should have her ‘tubes tied’ because her children were a burden on the government …”

—Los Angeles Times, June 19, 1975“And this lady came, I don’t remember seeing her face, I just remember her voice telling me, ‘Mijita, you better sign those papers or your baby could probably die here.’”

—Consuelo Hermosillo, interview 1“… the doctor would hold a syringe in front of the mother who was in labor pain and ask her if she wanted a pain killer; while the woman was in the throes of a contraction the doctor would say, “Do you want the pain killer? Then sign the papers.”

—Dr. Karen Benker 2

Trailer for the documentary No Más Bebés Por Vida, directed by Renee Tajima-Peña and produced by Virginia Espino and Renee Tajima-Peña, in association with the Independent Television Service and Latino Public Broadcasting.

Was the maternity ward at Los Angeles county hospital a border checkpoint for unborn babies? The documentary No Más Bebés Por Vida, 3 due to be completed this year, investigates the history of women of Mexican origin who contend that they were coercively sterilized at the Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center (LAC+USC) during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Many of these women spoke no English and have testified that they were prodded into tubal ligations during the late stages of active labor and as they awaited emergency Caesarean sections.

No Más Bebés Por Vida is the story of a group of mothers, young Chicano/a lawyers and activists, and a whistle-blowing doctor, who faced public exposure and stood up to powerful institutions in the name of justice. This essay is a glimpse both at that unfolding story and at the collaborative influences that have shaped the off-screen production. The project originated in the research of the historian Virginia Espino, who is the film’s co-producer, and it draws on the growing body of research into the history of sterilizations at LAC+USC by scholars such as Elena Gutiérrez and Alexandra Minna Stern. 4 Espino frames the sterilizations within theories of racial formation, both for the violation of the women—the brown body was policed by a racialized state even before birth—and for the emergence of Chicana feminist resistance. 5 Whereas the Mexican migrant worker historically has been predominantly male, the female represents the possibility of children, families, and future citizens (and by extension, the pollution of the gene pool)—fueling persistent anxiety over the immigrant. We may want the labor, but do we want the people—the families, the children, the lives—who come with it?

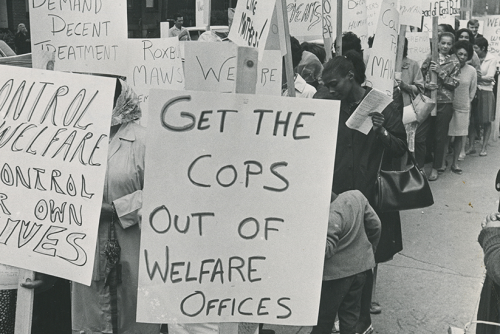

The film considers Gutiérrez’s argument that a “perfect storm” of sociopolitical factors—that is, the Zero Population Growth movement and concerns over welfare dependency and illegitimacy, bolstered by a huge influx of federal dollars to family planning—led to coercive sterilizations in Los Angeles and across the United States at the time. Elsewhere in the country, African American, Puerto Rican, Haitian, Dominican, Native American, and poor white women were also being targeted. 6 But, as Gutiérrez states, “for pregnant Mexican immigrant women in California during the 1970s, the issue of welfare and overpopulation were immutably tied to larger questions of citizenship and of who was rightfully deserving of social benefits such as medical care.” 7

Efforts to restrict and control the Latino population have long been intertwined with eugenics and social policy. According to Stern, the first challenge to California’s longstanding sterilization law to reach the appellate level was brought by Sarah Rosas Garcia in 1939, on behalf of her 19-year-old daughter. Stern found that long before the Madrigal v. Quilligan case, a disproportionate number of patients with Spanish surnames were being sterilized at “feeble-minded” facilities and were challenging the procedures privately and in the courts. 8 While scholars of the US eugenics movement contend that eugenic sterilization faded after World War II, Espino argues that federally funded family planning programs ushered in a culture of “back door” eugenics, where sterilizations occurred in apparently legal and voluntary procedures as hospital staff obtained consent either through coercion or without the patient’s knowledge. 9

Today, in an echo of the “population bomb” scare of the 1960s and 1970s, there is a new nativism, which has been coined as “the greening of hate” and cloaked in environmental alarm over climate change. 10 A steady drumbeat of public opinion and policy initiatives has generated proposals to limit prenatal care for undocumented women and reverse the 14th Amendment, the Constitutional guarantee of birthright citizenship. The enduring cultural fear of the hyperfertility of Mexican women from the eugenics era to the current cyber century is on view in the online shooter game, “Border Patrol,” which visually references the ubiquitous border-region road signs that depict a Mexican woman crossing with her children. The gamer is a Border Patrol agent targeting Mexican figures that race across the screen, including the pregnant, female “breeder.” When there is a direct hit, blood splatters from the infant cradled in her arms.

Where, then, did responsibility lie for the sterilizations at LAC+USC? The film attempts to navigate the gulf between accountability, as it is legally defined, and justice—the muddy waters through which policy, money, gender, race, and ethics travel from the public sphere to the maternity floor and which structure an intimate moment of a woman’s life: birth.

- Consuelo Hermosillo, video interview, 19 Oct. 2011.[↑]

- Elena R. Gutiérrez, “Policing Pregnant Pilgrims: Situating the Sterilization Abuse of Mexican-Origin Women in Los Angeles County,” Women, Heath, and Nation: Canada and the United States since 1945, eds. Georgina Feldberg, Molly Ladd-Taylor, Alison Li, and Kathryn McPherson, (Montreal: Mcgill-Queen’s UP, 2003) and trial transcripts, Madrigal v. Quilligan.[↑]

- Directed by Renee Tajima-Peña, produced by Virginia Espino and Renee Tajima-Peña, in association with the Independent Television Service and Latino Public Broadcasting.[↑]

- Alexandra Minna Stern, “Sterilized in the Name of Public Health: Race, Immigration, and Reproductive Control in Modern California,” American Journal of Public Health 95.7 (2005): 1128-1138. See also Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America, (Berkeley: U of California P, 2005); Virginia Espino, “Women Sterilized as They Give Birth: Forced Sterilization and the Chicana Resistance in the 1970s,” Las Obreras: Chicana Politics of Work and Family, eds. Vicki Ruiz and Chon Noriega, (Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Resource Center Publications, 2000): 65-82.[↑]

- Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1980s, (New York: Routledge, 1989[1986]).[↑]

- One of the most widely publicized was the case of two African American sisters, Mary and Minnie Reif, in Montgomery, Alabama. They were only ten and twelve years old when a hospital asked their mother to sign sterilization consent forms that she believed were consent forms for additional “shots.” Their mother could neither read nor write, and placed only an “X” on the form under the instructions of workers from the Montgomery Family Planning Center.[↑]

- Gutiérrez 2003.[↑]

- Alexandra Minna Stern, video interview, 8 Aug. 2011.[↑]

- Espino 2000.[↑]

- Priscilla Huang, “Anchor Babies, Over-Breeders, and the Population Bomb: The Reemergence of Natism and Population Control in Anti-Immigration Policies,” Harvard Law & Policy Review, 2.2 (2008).[↑]