Turning to the aesthetic in the case of queerness is nothing like an escape from the social realm, insofar as queer aesthetics map future social relations.

José Esteban Muñoz1

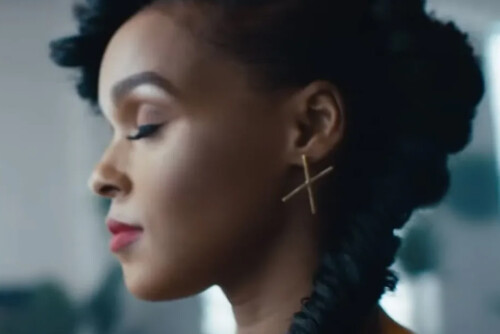

My photography project Queering the Archive: Brown Bodies in Ecstasy examines the intersections of race, sexuality, and eroticism as they relate to the in/visibility of black and brown queer bodies and subjectivities in South Africa. Through the photographic image, I disrupt the notion of discrete racial formations in South Africa by emphasizing the entanglements of history, memory, race, diaspora, and desire in the very constitution of racial categories. In my art, I respond to the near absence of visual representations of brown queer subjects in the public sphere. When the Indian emerges in visual representations, the focus is either on Mahatma Gandhi, anti-apartheid politics, or stereotypes of the middle-class Indian as the exploitative merchant. Such representations reproduce a heteronormative and homogenous perspective of the Indian experience, one that renders class stratification and gender and sexual difference invisible. Such representations also offer a limited perspective on Afro-Indian relations in South Africa that over-emphasizes heteromasculinist tropes. My work centers alternative identities and experiences by focusing on the queer of color subject. I turn to aesthetics and eroticism to disrupt the heteropatriarchal gaze and its violence against (queer) bodies of color.

Visibility and legibility are important themes in my work, and in this project I create new conceptual pieces by layering, juxtaposing, and blending portrait photos from my family album, with color digital photographs shot in a studio2 I also use other historical materials collected over the years by my grandparents and parents that constitute a family archive. Specifically, I focus on the Indian “pass” document, an official form of identification issued by the Protector of Indian Immigrants. Pass documents from the 1930s and 1940s contain a wealth of information and function as an alternative archive of family, community, and nation. They include indentureship numbers, tattoos, and other bodily markings used to identify Indian immigrants in the colonies. They also functioned as marriage certificates and records of birth and deaths of children. Through the indentureship numbers it is possible for one to trace one’s roots back to India, as the numbers listed correspond with ship lists and logs housed at the Gandhi-Luthuli Documentation Center at the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal. The wealth of information within these documents speaks to the obsession with the body of the colonized as a site of racial, ethnic, and sexual difference, and emphasizes the production of the Indian body through the visual economies of colonialism and apartheid. In some of the large-scale visual assemblages I create for this project, I superimpose pass documents onto brown, black, and white bodies to emphasize both the manner in which the body functions as an archive and repository of history and memory, and also the power relations between white, brown, and black. By “assemblages,” I refer to my artistic practice of creating something different by fitting together objects (in this case, photography and documents) that individually can appear unrelated. For me, assemblages emphasize accumulation and sedimentation, and hint at the multiple layers and fragments that constitute (diasporic) subjectivity. In my assemblages, the emphasis shifts from “roots to routes,” to evoke Paul Gilroy, in order to trouble the idea of an essential Indian identity – or, for that matter, essential white, colored, or black African identities – and show how these racial categories are produced and constantly reproduced in relation to each other.3

Another recurring visual motif in my art is sugarcane, which is a direct reference to the history of British colonialism and Indian indentured labor in South Africa. I use the aesthetics of sugarcane to create a transnational and diasporic connection between Indian descended communities that constitute the old Indian diaspora.4 The sugarcane connects Indian diaspora communities from South Africa to Trinidad, Guiana, Mauritius, and Tanzania.

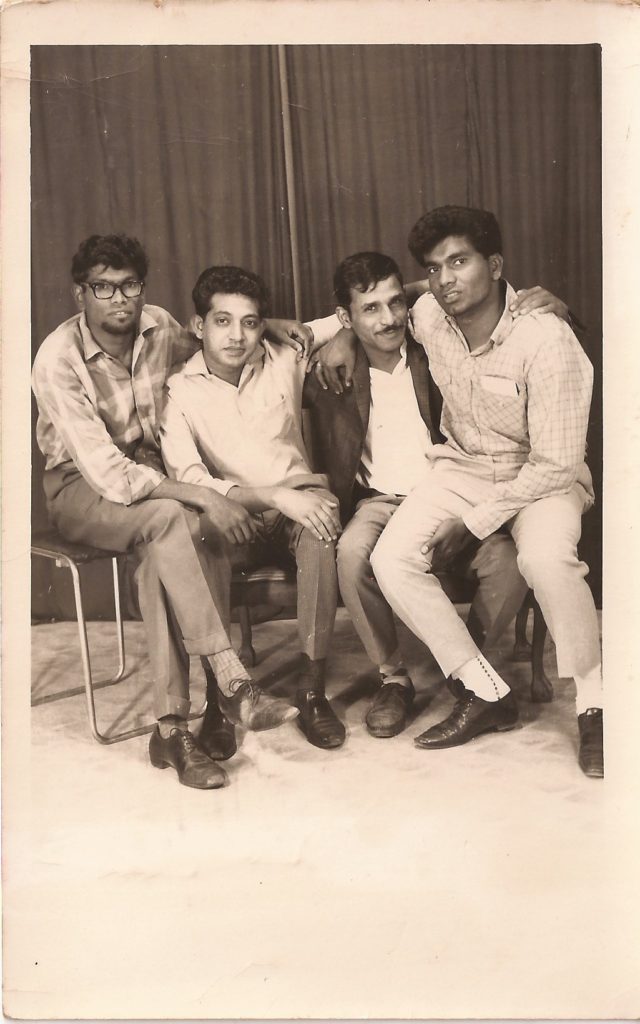

My family albums influence the contours of this project. I particularly draw on those compiled by my grandparents, who over the years obsessively collected all kinds of photographs of family members and extended family and friends, creating a personal archive that includes one of the only representations of our earliest ancestors who arrived in South Africa as indentured workers. There was something pleasurable about looking at these photographs, which offered me an alternative site of identification while growing up in the 1980s and 1990s in a changing South Africa. In these albums, I was most fascinated with the large number of photographs of Indian men. Many show men in pairs or groups, posing for the camera in studios or in more intimate spaces like the home. These images offer a glimpse into their lives and represent the intimacies shared between men of prior generations, images that are largely absent within visual cultural representations of Indian South Africans. Through my family album, I accessed an archive that points to transient moments of male-male intimacy that became the foundation for this project. For me, the flashes of intimacy (evidence of homosociality) in the black and white photographs disrupt normative notions of race, gender, sexuality, and community. In older photographs, men stand next to each other, hands, shoulders, and bodies just touching, facing each other or gazing into the camera. In a set of later photographs, the men are comfortable and at ease with each other. The intimacy extends beyond almost unseen flashes of intimacy where just hands or legs slightly touch. In many photographs, men sit on top of each other with their legs entwined and arms hung across their companion’s shoulders, revealing something “queer” about such masculine expressions.

The people in these albums, my blood ancestors, were the abject subjects of Indian indentureship and apartheid, but there was something about their confident poses, their direct gazes, their immaculately dressed bodies, the smiles on their faces, and the mischief in their eyes that appealed to me, creating an affective relationship and identification with these people who had survived under oppressive conditions and histories of violence. The images I found within the family album humanized Indians in their everyday practices of family and community formation and offer a very different perspective of the Indian experience in South Africa, which disrupts official representations employed by the colonial and apartheid-era states.

The earliest photographic representations of Indian indentured men in South Africa can be traced to a collage of photographs taken by the British colonial state as a form of identification that established the unequal relationship between the British (colonizer) and the Indian indentured subject (colonized). In these photographs, which resonate with other official state identification photography, the men look directly into the camera while holding their indenture numbers, subjected to the colonial gaze. This collage consists of twelve bare-chested men, their ribs sharply visible and their eyes sunken. Their emaciated bodies testify to their arduous journey across the kala pani. Although their ages are unknown, many look as though they are barely adults. Riason Naidoo, artist and curator, writes:

The figures [of the indentured Indian men] are replicated like wallpaper, suggesting a continuity, an infinite number of other laborers beyond the borders of the image, while also underlying their presence in the colony as mere number – commodities in the sugar industry. The administrative categorization of the “Indian” labourer emphasizes the unbalanced power relationship between colonizer and the colonized, capitalist and worker, viewer and subject. The head-on portraits evoke comparison with prisoner classifications, where the subjects can offer only a docile glance in the face of the more powerful gaze of the camera and behind it the paternal state.5

This form of state photography functioned like the Indian pass document to render “passive the ‘working classes, colonized peoples, the criminal, poor, ill-housed, sick or insane.'”6 In contrast to the official gaze of the colonial and apartheid state, the photographs found in my family album reveal the manner in which these subaltern men and women sought to reconstruct and redefine themselves outside of the colonial gaze, reiterating the importance of the visual in the formation of the subject and community. These people where “disidentifying” with the state by negotiating their own image making. José Muñoz theorizes disidentification as “the survival strategies the minority subject practices in order to negotiate a phobic majoritarian public sphere that continuously elides or punishes the existence of subjects who do not conform to the phantasms of normative citizenship.”7 The alternative histories, pleasures, and desires evident in these photographs and in the album itself points to the labor of negotiating the violence of exclusion and abjection created through colonialism and apartheid. The family portraits shift the optic of these colonized peoples from victims to subjects with agency.

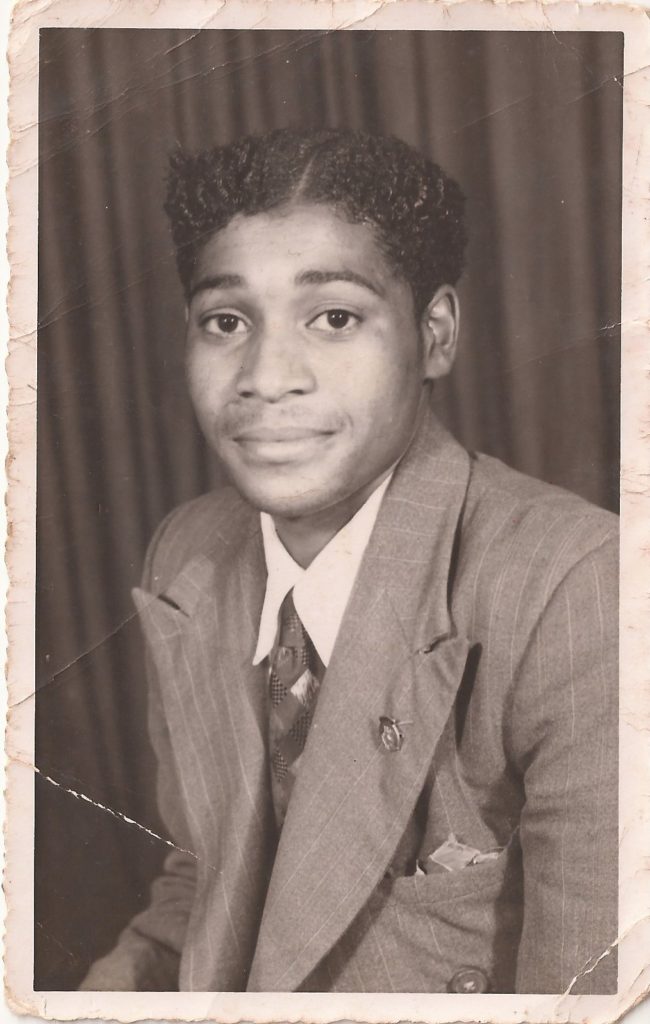

Over the years, I became familiar with my family albums, which were stored in a cupboard; hidden away among winter blankets, duvets, and old clothes; and only retrieved when extended family members visited. I still remember relatives’ animated conversations as they looked through the leaves of the albums. I was entranced with the histories, narratives, and memory slippages that the albums generated. The larger collection of family photographs in these albums are evidence of the lives lived by adults and children during the colonial and apartheid eras and reflect the hopes, desires, and pleasures of a community that was situated, through colonial and apartheid-era politics, interstitially between whites and black Africans. As my interest and intimacy with these photographs and other documents developed over the years, so too did my interest in the relationship between these images and broader notions of race, gender, sexuality, and the nation. Very early on, I realized that the recognition I experienced through the family album was incomplete and fragmented because these albums reproduced a very insular notion of the Indian family and community, firmly establishing the “color line” and reinforcing the boundaries between black, Indian, and white. Although I searched, the album anxiously tried to conceal traces of racial and sexual difference. On closer inspection, I found two images that hinted at more complex forms of racialization within the Indian community. I found one portrait photograph of a white man, an evangelical pastor who was responsible for the conversion of a large number of Indians to Christianity in this small community. The white missionary represents the civilizing mission of colonialism in which Christianity was employed to create proper, respectable subjects out of the colonized masses. Religion, whether Christianity or Islam, imposed a moral framework onto colonized subjects that regulated the domain of gender and sexuality, and therefore the arenas of pleasure and eroticism, by emphasizing heterosexuality as normative. Furthermore, sexuality in the “Christian context … [was] conceived as an issue of morality and sin” and only sanctioned sexual relations between married men and women.8 These Christian and Muslim logics also regulate the boundaries of race. The wedding and family portraits scattered throughout the album reinforce the construction of a heteronormative Indian community and kinship through the photograph. The many wedding portraits appear alongside the homosocial representations of men, but have a privileged position and greater visibility that obscures the traces of intimacy between men. Such dynamics reiterate heterosexuality as the foundation of this abject community even though non-normative relationships between Indian indentured men and women are well documented both in historical archives and also in oral narratives that circulate within families.

I also came across one photograph of a man who appears to be mixed-race and whom no one living is able to identify. The mixed-race man in the album pushes the boundaries of Indianness to its limit and hints at the messiness of desire, eroticism, and racialization. Even though the photo album anxiously desires the reproduction of ethnic purity, whiteness and blackness haunt the formation of Indian identity and exist within its domain, even though they are located peripherally and can easily be rendered invisible. These photographs, one of the white evangelical pastor and one of a mixed-race man, hint at the complex entanglements between black, white, and Indian in the daily lived experiences of this community.

In this body of work, I turn to a queer analytic and aesthetic in order to destabilize and denaturalize racial categories. One of my objectives in creating these visual assemblages is to disrupt the absences of race and sexuality in the family album. My creative choice to superimpose and juxtapose the black and white archival photographs with the color studio photographs was influenced by the flashes of male-male intimacy I noticed in the black and white images. The color photographs reimagine these moments of intimacy. By drawing out aesthetically queer male desires in the color photographs through superimposing them onto the black and white images, the project disrupts the heteronormative logics of both the Indian community and also the South African nation. In this photography project, I argue for the political potential of aesthetics to destabilize normative racial formations in South Africa that were based on the colonial and apartheid-era policies of racial segregation and “separate development.” By focusing on the aesthetics of transgressive erotics in my color photographs, I emphasize the traces of queer eroticism, which includes interracial erotics, in the photographs from my family archive. In the family album, the photograph of a mixed-race family member is marginal. Yet, in my visual assemblages I center interracial queer intimacy to emphasize the manner in which it is constitutive of racialization in South Africa.

The aesthetics of interracial eroticism, historically produced as transgressive in South Africa, is central to my politics of disruption. Scholars of race and sexuality, particularly women of color feminists and queer of color theorists, argue that it is “quite nearly impossible to separate ideas about race from ideas about sexuality.”9 Indeed, the threat of interracial eroticism, particularly between black African men and white women, shaped many colonial and apartheid-era policies, demonstrate the messy entanglements between racial formations and desire, and capture what Sharon Holland defines as the “erotics of racism.”10 For Audre Lorde, the erotic is powerful; she writes that “our erotic knowledge empowers us, becomes a lens through which we scrutinize all aspects of our existence, forcing us to evaluate those aspects honestly in terms of their relative meaning in our lives.”11 Alliyyah Abdur-Rahman argues that “there is power in the erotic, and in sexual non-normativity, to narrate a world – or, more specifically, to narrate the world of particular marginalized, minoritized subjects and to remake it.”12 Influenced by Lorde and Abdur-Rahman, my use of “transgressive erotics” as an aesthetic and analytic in my project allows me to unpack non-normative desires and pleasures that are rendered illegible and mostly obscured through the heteronormative logics of the family album. The family album reproduces the logic of the nation and community by relying on the “fantasy of sameness, wholeness, or completeness.”13 By reading for flashes of the homoerotic in the black and white photographs to hand, this body of work critiques the violence of normativity in post-apartheid South Africa that obscures previously marginalized minorities like Indians and coloreds and black and brown queers.

Although apartheid-era policies in South Africa anxiously monitored and maintained the separation of racial groups (white, black, Indian/Asian, colored), various intimacies developed between groups, both politically and in peoples’ everyday lived experiences, which point to the entanglements of race and racialization with desire and eroticism. Intimacy provides a framework with which to examine the “volatile contacts of colonized people.”14 Scholars like Lisa Lowe, Gayatri Gopinath, and Vanita Reddy, for instance, draw on this notion of intimacy to understand the “possibility of cross racial alliance that emerge from this contact.”15 Reddy also understands intimacy as allowing us “to access however contingently and ephemerally, forms of relationality that … remain ‘inaccessible and unseen’ … Intimacy gives expression to tacit, minor, or ephemeral affective relations … that may surface only within the domains of the aesthetic and representational.”16 For me, in my critical creative practice and academic writing, the aesthetics of queer racialized erotics, a form of transgressive erotics, not only disrupts but also situates aesthetics centrally to an alternative imagination of Afro-Indian relations and racial formations that gesture toward the future. Keguro Macharia reminds us that queer theory and African writers have turned to aesthetics: queer studies scholars like “Leo Bersani, Tim Dean, Jack Halberstam, and Lee Edelman … have privileged aesthetics as a mode to access and forge ethical relations. Crucially, African writers such as Chinua Achebe, Ken Saro Owour, Yvonne Vera, and Yvonne Owour similarly use aesthetics to suggest possibilities foreclosed or absent in official political discourses.”17 My turn to aesthetics functions similarly to create new possibilities by reading against the political and the normative in the South African context. I also employ queer racialized eroticism in a disidentificatory manner. If normative Indianness in South Africa is overrepresented through Gandhi and heteropatriarchal Afro-Indian political affiliations formed through anti-apartheid politics, this project disrupts these formations through the aesthetics of queer racialized erotics.

The layering of the archival images with the contemporary digital photographs in my visual assemblages has a haunting effect that connects the past with the present. The superimposition also speaks to the sedimentation of histories, memories, and desires that braids together black, brown, and white, making visible the intimacies that connect us across time and space. These visual assemblages belong as much to the past as to the present, and simultaneously disrupt these temporalities by emphasizing alternative forms of social relations that destabilize normative social formations. My project invites viewers to move into the space of the imagination and to allow themselves to become another sediment in this visual experience grounded in pleasure and aesthetics.

- José Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 1. [↩]

- Zewande K. Bhengu shot the color digital photographs in Johannesburg in 2013. [↩]

- Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993). [↩]

- Vijay Mishra, “The Diasporic Imaginary and the Indian Diaspora,” Asian Studies Institute Occasional Lecture, August 29, 2005, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/11243784.pdf?repositoryId=343. [↩]

- Riason Naidoo, The Indian in Drum Magazine in the 1950s (Cape Town: Bell-Roberts Publishing, 2008), 13. [↩]

- Ibid., 14. [↩]

- José Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 11. [↩]

- Signe Arnfred, “Re-thinking Sexualities in Africa: Introduction,” in Re-thinking Sexualities in Africa, ed. Signe Arnfred (Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute, 2004), 14–15. Also see Deeva Bhana et al., “Power and Identity: An Introduction to Sexualities in Southern Africa,” Sexualities 10 (2007): 131; Neville Hoad, African Intimacies: Race, Homosexuality and Globalization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007); Mark Epprecht, Hungochani: The History of a Dissident Sexuality in Africa (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004); Mark Epprecht, Heterosexual Africa? The History of an Idea from the Age of Exploration to the Age of AIDS (Columbus: Ohio University Press, 2008). [↩]

- Aliyyah I. Abdur-Rahman, Against the Closet: Black Political Longing and the Erotics of Race (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 2. Also see Roderick Ferguson, Aberrations in Black: Towards a Queer of Color Critique (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2003); Black Queer Studies: A Critical Anthology, ed. E. Patrick Johnson and Mae G. Henderson (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), Omisek’eke Natasha Tinsley, “Black Atlantic, Queer Atlantic: Queer Imaginings of the Middle Passage,” GLQ 14, 2–3 (2008): 191–215; Matt Richardson, The Queer Limit of Black Memory: Black Lesbian Literature and Irresolution (Columbus: Ohio State University Press). [↩]

- Sharon Patricia Holland, The Erotic Life of Racism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012). [↩]

- Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audrey Lorde (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 2007), 57. [↩]

- Abdur-Rahman, Against the Closet, 2. [↩]

- Gayatri Gopinath, “Archive, Affect, and the Everyday: Queer Diasporic Re-visions,” in Political Emotions: New Agendas in Communication, ed. Janet Staiger, Ann Cvetkovich, and Ann Reynold (New York: Routledge, 2010), 167. [↩]

- Gopinath, “Archive, Affect and the Everyday,” 166. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Vanita Reddy, “Afro-Asian Intimacies and the Politics and Aesthetics of Cross-Racial Struggle in Mira Nair’s Mississippi Masala,” Journal of Asian American Studies 18, 3 (2015): 233–63. [↩]

- Keguro Macharia, “Queering African Studies,” Criticism 51, 1 (2009): 157–64. [↩]