A Life Journey with At-Risk Families:

PB&J Family Services, Inc.

Albuquerque, New Mexico is a growing Southwestern city, home to a

diversity of cultures in a colorful, vibrant setting. It is also home

to a unique non-profit organization, developed over the last 37 years to

serve at-risk children and families. While directly serving a specific

community, systems and policies have emerged that have resulted in

cutting-edge practices for those who frequently have no voice at policy

tables.

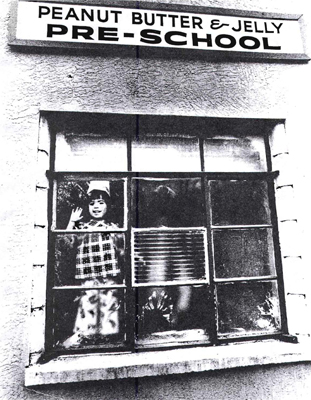

PB&J Family Services, Inc. (affectionately known as Peanut Butter and

Jelly) was founded in 1972 in Albuquerque's rural Southwest valley in

response to a scarcity of services for young children. Its first target

population was children of mothers being treated at the county mental

health center. It then grew to inform child welfare practices more

widely in the Albuquerque area.

I write this article as PB&J's co-founder and Executive Director

emeritus, having served as its ED for 35 years. PB&J defines its

mission to serve at-risk children to grow to their full potential

within nurturing families in a supportive community. Over the years,

the effort of helping our families to become more nurturing has faced

significant challenges. Creating supportive communities and families has

meant incorporating the spaces of prisons and jails into family and

community life—an effort with countless barriers. The growth of PB&J

has been, in every instance, a response to the needs of children and

families that have emerged in a changing society.

Although PB&J now provides services for nearly two thousand highly

challenged lives, its beginnings were rooted within a handful of mothers

in the early 1970s when I was employed at the University of New Mexico's

mental health center. With interest, I observed these young women

coming in for treatment. They'd sit around a large table doing arts and

crafts as a nurse walked around the table injecting each woman with a

psychotropic medication. We used Prolixin at the time, which was

thought to be an effective chemical combatant for clinical depression.

After the group activities, the women were given a vial of Thorazine

tablets to offset the side effects of the Prolixin, and we wouldn't see

them until their scheduled treatment the following week.

I wondered, who are these women? Are they parents? Who are they

going home to? Whose lives do they affect? Who affects theirs? In

those days, we didn't have public transportation in Albuquerque's rural

valley areas, so I began asking the women if they wanted rides home.

One by one they accepted, and, as I left them at their front doors, I

realized that every woman was a parent of very young children.

Having been a teacher, I decided to start a small school for these

kids in order to get them out of the dark environment in which they

lived, and provide some stimulation and learning. With my friend and

co-worker, a child development associate named Christine Ruiz, we

located donated space in a storage room, cleaned it up, received donated

crayons, paper, puzzles, tables, chairs, and snacks, borrowed a bus

every morning from the mental health center, and off I'd go around town

picking up children to take them to their new school.

The children's response was nothing short of amazing. These quiet,

withdrawn children became animated and active. They danced, sang, and

played. As time passed, however, unexpected and unintended results

occurred. Children began to show signs of significant physical abuse.

Page: 1 |

2 |

3 |

4

Next page

|